10 The Pompeii Shop

A group of customers went shopping in AD 79 and never made it out of the shop alive. The infamous volcanic eruption of nearby Mount Vesuvius hit the shop near the outskirts of Pompeii and overwhelmed them. In 2016, a mixed team of French and Italian archaeologists rediscovered the unlucky patrons, among them a teenage girl, while excavating the Herculaneum port. The other people who died there were also young. In addition to their remains, the diggers found gold coins and a gold necklace pendant that somehow got overlooked by looters. While investigating the shop, researchers found telltale signs that somebody ransacked the business during the disaster, looking for things to steal. What product or service was sold at the shop is not entirely clear. However, it appeared to have been some sort of workshop with an oven, possibly to forge objects made of bronze. The same dig uncovered a second shop with a well and a spiral staircase, but researchers are presently at a loss about what type of business was conducted at the site.

9 The Flint Factory

In 2016, archaeologists were shoveling beneath an abandoned kindergarten in Bulgaria. When they found flint, it didn’t take them long to realize that the different-sized pieces meant a lot of tool-shaping once occurred there in antiquity. The more they looked, the more the scope of the factory became apparent. This wasn’t just a hearth around which a few people had gathered and chipped some tools for themselves. It was literally a production line manned by individuals specialized in different aspects of product creation. Ancient employees toiled 6,500 years ago and mass-produced items such as flint knives. Moreover, experts believe that this was a prehistoric exporting business. No completed tools were found. The only signs of stone were flint cores, chips, and weapons in different stages of production—but none that were finished. This supports the idea that as soon as a knife or ax was done (or a whole batch of them), they were moved elsewhere to be sold. Another interesting discovery at the factory was a grave dating back to the same time it was still in use. Inside was a man clasping a stone ax scepter.

8 Nonstick Frying Pans

A first-century Roman cookbook called De Re Coquinaria mentioned cookware that nobody could find. Called Cumanae testae or Cumanae patellae, these nonstick wonders were described by the author as best suited for cooking chicken stew. In 1975, archaeologist Giuseppe Pucci suggested that a brand of ceramics called Pompeian Red Ware was the Cumanae described in the ancient cookbook. Backup for his theory arrived in 2016, when a trash site near Naples produced 2,000-year-old pottery fragments. Nearly 50,000 pieces of pots, lids, and frying pans were recovered. Just like Pompeian Red Ware, most were coated with a red-slip layer on the inside to prevent food from burning to the bottom. The fragments at the dump site were likely freshly made wares that didn’t make the cut or broke during production. What supports Pucci’s claim is the fact that the city of Cumae, which gave the mysterious kitchen utensils their name, was located just 19 kilometers (12 mi) from Naples. The city once mass-produced and exported pottery to places as far-flung as Africa as well as across Europe and the Mediterranean.

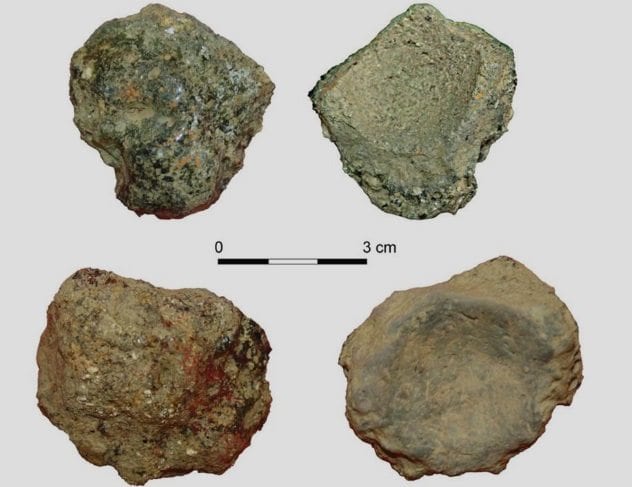

7 The Naxos Mine

A prehistoric workshop was discovered in 2013 on the Greek island of Naxos. The extraordinary thing was that it appeared to have been in use for thousands of years. Also, it wasn’t owned by modern humans. Earlier hominids had passed something on to each successive generation, something critical for survival: the location of a seemingly endless supply of chert. The valuable stone was necessary for the creation of tools and weapons. On Naxos was essentially a 118-meter-high (387 ft) hill consisting almost entirely of the sought-after raw material. Called Stelida, the site was first discovered in 1981 by a survey on the northwestern coast of the island. The 2013 excavations found the rubble left behind by toolmakers who mined the hill from the Paleolithic era right through to the Mesolithic. There was also ample evidence that tools and weapons were created at the site, although none have been found so far. The discovery could also change how researchers piece together human migration. This area of Greece is now being studied as previously unknown route that early humans took to spread from Asia to Europe.

6 The Galilee Kiln

The ancient world needed places to manufacture ceramic, and Galilee was no different. However, one pot workshop found in the modern-day town of Shlomi is unique. Found in 2016, what made it so special was its industrial oven. Unlike other kilns made of stone or even mud, this one was cut straight into the bedrock. Archaeologists found that the geology of the area likely accounted for this unusual firing pit. The region had a chalky type of bedrock that was soft enough to be shaped into the desired form while resistant enough to endure the heat of the pottery-making process. The shop was active around 1,600 years ago, during Roman times. By studying the ceramic remains in the double-chambered kiln, it was determined that the owners focused mainly on storage jars and containers designed to hold oil and wine. One box was used to feed a fire with branches and tinder, while the other chamber was used to harden the clay.

5 Foundry Complex

A happy accident occurred in 2016 when a group of people headed toward a sightseeing area on Lake Baikal in Siberia. Many tourists had trampled this route before, but these weren’t just any visitors. Noticing the slag and clay on the path, the trained eyes of the archaeology party quickly realized that something was up—or more like down. Soon, a medieval foundry was unearthed. Used to make weapons, the complex was highly advanced and professional. A pair of rare, ancient stone furnaces were once part of a skilled metallurgic operation that churned out weapons, metal parts for horse tack, clothing, and even sickles. The Baikal region has a rich history of working with metal and exporting the excess. However, the new foundry, which dates to around AD 1000, shows a level of technology that’s a step above anything the experts have ever seen before. The location was well-chosen, high on a hill, in order to harness the wind to help with the combustion process. The ancient blacksmiths may have been the Kurykan people, who were known for their expert metallurgic abilities.

4 The Glass Community

In prehistoric Poland, an isolated community left behind a fascinating part of their identity. Apart from a few houses, artifacts found on Mount Grojec in 2017 showed that they were glassmakers. There were no completed items that might have placed them instead as glass buyers, but there were artistic blunders, slag (melted waste glass), and half-glass, ready to be heated and shaped. The only finished product found were small beads. The discovery of the 2,000-year-old factory is an important one for Polish history. Not only is this probably the oldest glass workshop found in the country, but it’s also the only proof that glass processing occurred in Poland much earlier than the Middle Ages, which is when conventional thought believes the craft blossomed. There are numerous furnaces at the small village, and some were for forging metal as well. The pieces of raw glass were of particular interest. The half-processed material was acquired from somewhere, but researchers aren’t sure who the suppliers were. It’s not even certain who the villagers were.

3 Christian Winery

In 2013, a Byzantine-era wine factory was discovered in Israel. Located near the archaeological site of Hamei Yo’av, the ruins covered enough area to indicate that the residents of the settlement produced wine on a large scale. Spanning over 100 square meters (1,100 ft2), the complex consisted of sections where grapes were dumped after being delivered to the factory. The fruit was probably also left to ferment in these compartments. In the middle was a vast floor constructed at a sloping angle to allow the juice from pressed grapes to flow into holding vats. Archaeologists believe that besides producing the best wine they could, the workers turned grape waste into secondary products, such as vinegar and a less refined “pauper’s wine.” The owner might also have been Christian. One of the artifacts found at the wine press was a small ceramic lamp fashioned in the shape of a church. The hollow artifact was carved with crosses that would glow once a flame was lit on the inside.

2 The Surgeon’s Room

When archaeologists cleared away ancient earthquake rubble in Cyprus in 2017, they found what they believe to be a doctor’s office. Found near the city square of Nea Paphos, it had several rooms. In one of them, the team found a glass unguentarium in mint condition. Such bottles were used to store liquids like oils, perfumes, and medicines. But the best discovery was a surgeon’s 2,000-year-old tools. The surgical instruments were all made from metal. One was iron, and the other five were bronze. They included a long, narrow spoon, pliers, and devices most likely used to set a patient’s broken bones. Like the bottle, the set was well-preserved. Coins found in a second room roughly date to the time when a big earthquake hit Nea Paphos in AD 126, collapsing the building that housed the doctor’s office as well as other businesses. The debris was never cleared away or replaced with anything else, which helped to seal the artifacts away safely.

1 Revenue Office

Nicopolis ad Istrum was a city founded by Roman emperor Trajan in what is modern-day Bulgaria. Raised around AD 102, it was sacked by several different barbarian hordes throughout its long history and was eventually settled by the Bulgarian Empire between the tenth and 14th centuries. Like any well-run Roman city, commerce was tightly governed by the powers that be. After its ruins were found in 2016 near Veliko Tarnovo, the city proved to be huge. One fascinating building was a public place that appeared to have been the office of that eternal unfavorite: the tax man. Inside, archaeologists found stone weights and measuring devices in large numbers. Called egzagia, they were compulsory for anyone selling goods anywhere in the city so that buyers would not be deceived. The team that investigated the site believe that the building was a tax agency and government center where trade in Nicopolis ad Istrum was strictly controlled. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages