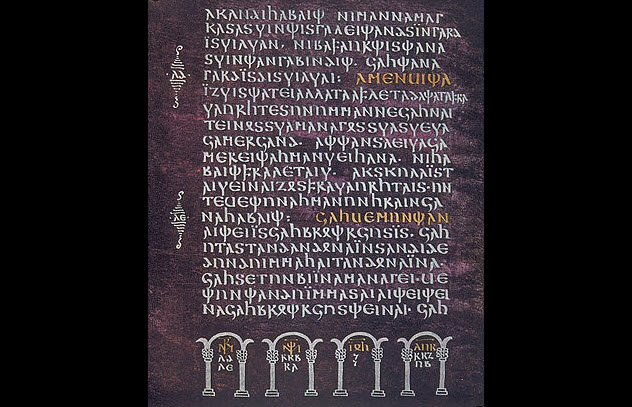

10 Gothic Bible

Language: Gothic The Gothic Bible (aka the Wulfila Bible) was produced in AD 350. Although only fragments survived, many of those pieces were edited during the fifth century by a Catholic priest named Salvian, who claimed that they were full of blasphemous phrases. The main reason for this was that Wulfila, like many Goths, was an Arian—someone who believed that Christ was not God but a created being. This was anathema to Catholics and their fervent belief in the Holy Trinity. Translated in Gothic as “Little Wolf,” Wulfila was a bishop and missionary who was raised as a Goth. At age 39, Wulfila decided that it would be easier to convert the Gothic people to Christianity if they had a Bible in their own language. As there was no alphabet and the Gothic language consisted of few words, he had to create most of it himself. Adapting the alphabet used by the Greeks, Wulfila also invented most of the words used to convey abstract ideas within the Bible. The entire book was translated—with the notable exceptions of 1 Kings and 2 Kings. The historian Philostorgius explained these omissions: The Goths were “fond of war and were in more need of restraints to check their military passions than of spurs to urge them on to deeds of war.”

9 Hieroglyphs In The Tomb Of Seth-Peribsen

Language: Egyptian Although examples of single Egyptian hieroglyphs may be found elsewhere, the earliest known examples of full sentences of Egyptian hieroglyphs are located in the tomb of Seth-Peribsen, a pharaoh of the late second dynasty around 2740 BC. Seth-Peribsen, the first pharaoh to use a Seth name rather than a Horus name, was buried at Umm el-Qa’ab, an ancient necropolis where many early dynastic kings were buried. However, some doubts about his reign persist because his name was omitted from king lists written during later dynasties. To refute that claim, some scholars point out that many priests during the fourth dynasty were dedicated to his funerary cult, leading some to also believe that Seth-Peribsen was a celebrated ruler of both Upper and Lower Egypt. Confirming that point, the clay seals in Seth-Peribsen’s tomb read as follows: “Sealing of everything of Ombos (Naqada): He of Ombos [Seth] has joined the Two Lands for his son, the Dual King Peribsen.”

8 Praeneste Fibula

Language: Latin The Praeneste fibula (aka the brooch of Palestrina) is a golden brooch with a troubled history. In 1887, a German archaeologist named Wolfgang Helbig presented it to the public for the first time at the German Archaeological Institute. He claimed to have received it from a friend who found it in Palestrina, a still-occupied ancient city about 30 kilometers (20 mi) east of Rome. Eventually, that unidentified friend was revealed to be Francesco Martinetti, an accomplished forger. Helbig was also dogged by suspicions of shady dealings, although much of them came well after his death. Questions arose about the Praeneste fibula because there was an engraving on the 10-centimeter (4 in) brooch: “Manios had me made for Numerius.” Dating back to the seventh century BC, this is the earliest known example of Latin writing. However, as early as 1905, people suspected that the engraving was faked. In 2011, scientists used new testing methods and declared that the Praeneste fibula was genuine “beyond any reasonable doubt.” Their evidence focused on microcrystallizations of gold in the inscription that could only have formed after centuries of existence. A 19th-century forger could not have faked this.

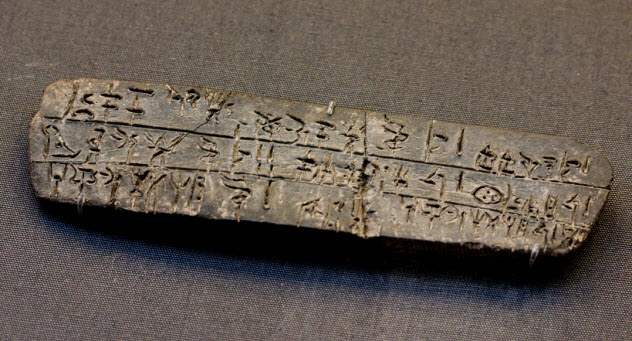

7 Knossos Tablets

Language: Mycenaean Greek (Linear B) Mycenaean Greek, the oldest attested form of the Greek language, is also known as Linear B, especially when referring to the writing system. Scholars generally agree that Linear B was derived from a slightly older syllabic script known as Linear A. Linear A has been dubbed the “Minoan language” because it is found in the ruins of the Minoan civilization. For now, it’s still untranslated. However, Linear B has been translated, with nearly 200 signs found on clay tablets. These symbols range from numerals to depictions of various objects. The majority of clay tablets with Linear B inscriptions have been discovered in Knossos on the island of Crete and in Mycenae and Pylos on mainland Greece. In 1900, British archaeologist Arthur Evans uncovered a treasure trove of tablets dating back to 1400 BC. However, the script remained undeciphered for years. That task was eventually undertaken by amateur Michael Ventris, a mostly self-taught scholar who had seen the tablets when he was a schoolboy. The tablets were finally translated more than 50 years after their discovery. They were used mainly for recording the disbursement of goods.

6 Behistun Inscription

Language: Old Persian For scholars, the Behistun Inscription is as invaluable in deciphering cuneiform script as the Rosetta Stone is in translating Egyptian hieroglyphs. Widely believed to be the earliest example of Old Persian, the Behistun Inscription is a rock relief carved into a cliff at Mount Bisotoun (“the place of God”) in Iran. Written by Darius the Great after his coronation in 522 BC, the Behistun Inscription is less of a historical document and more of a triumphant autobiography which sometimes borders on outright propaganda. Old Persian, a forerunner of the modern language of Farsi, only lasted a few hundred years. Then the natural evolution of language produced something different enough to be considered new. The meaning behind the words—as well as the true identity of the author—faded into obscurity until Sir Henry Rawlinson, the father of Assyriology, deciphered the text.

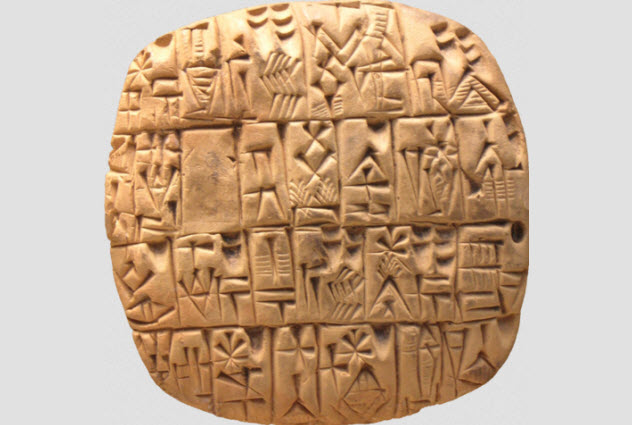

5 Instructions Of Shuruppak

Language: Sumerian The Instructions of Shuruppak may be the greatest piece of Sumerian wisdom literature, which are writings intended to teach about the divine or how to be virtuous. They were written by an eponymous king and dedicated to his son. Similar to Proverbs in the Jewish and Christian tradition, the Instructions of Shuruppak contain lists of advice ranging from the moral to the practical. Although the exact date of authorship is unknown, extant copies found in the ruins in Abu Salabikh have been dated to 2500 BC. The Instructions of Shuruppak were a popular teaching tool as shown by the relatively large number of copies found at other sites, with some even dating to 1500 BC. The later version was in Akkadian, which had supplanted the Sumerian language as the premier spoken language by that time. This occurred mainly due to the conquests of Sargon of Akkad.

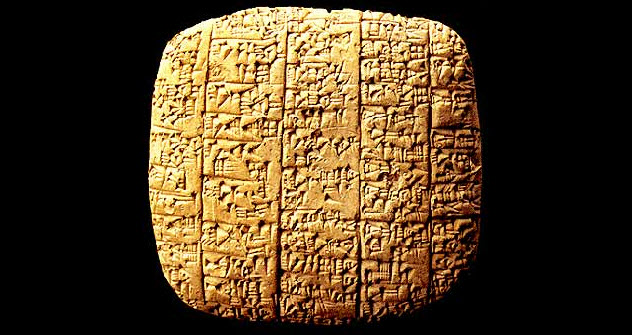

4 Ebla Tablets

Language: Eblaite Found in the ancient city of Ebla, Syria, the Ebla tablets numbered more than 11,000 and were discovered in situ, an archaeological term that means “in their original positions.” Pablo Matthiae, an Italian archaeologist, discovered them in the mid-1970s. They proved invaluable for revealing the history of an extremely prosperous kingdom throughout the third millennium BC. Eblaite, the second earliest attested Semitic language after Akkadian, is probably the most ancient language to survive in substantial form. Like many of the Mesopotamian languages, the cuneiform used by the citizens of Ebla drew heavily on the Sumerian language. Due to this and the sheer number of tablets found in Ebla, scholars have used the language to assist in the comparative study of other Semitic languages, including Hebrew. In addition, the Ebla tablets attracted a lot of controversy because many claims were made about their confirmation of cities mentioned in the Jewish tradition. For years, the tablets were purported to contain the earliest mentions of many cities, including Jerusalem. But that has been proven to be incorrect.

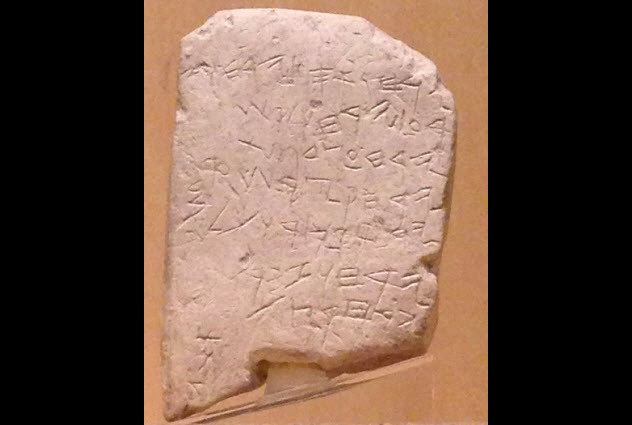

3 Gezer Calendar

Language: Hebrew The Gezer calendar is not a calendar in the sense in which we use them now, but it did contain the earliest example of the Hebrew language. Written on a piece of limestone that has been dated to the late 10th century BC, the Gezer calendar derived its name from the annual agricultural cycle written on it. In 1908, the calendar was discovered by Irish archaeologist R.A.S. Macalister in the ancient Canaanite city of Gezer. The calendar has seven lines of text. Each line references one or two months and the appropriate action to be taken. For example, the month of Nisan is associated with the harvest of flax. However, the true purpose of the Gezer calendar is unknown. Some scholars have suggested that it might have been a schoolboy exercise or a popular folk song.

2 Markings On Oracle Bones

Language: Chinese The oracle bones, which bore the markings of an ancient form of written Chinese, were constantly being uncovered. However, nearly all of them were found by peasants. Some people who were ignorant of the oracle bones’ value ground them into poultices to heal various ailments. Dating back to 1200 BC, these bone fragments from turtles or buffalo were inscribed with different texts and then used by the kings of the Shang dynasty to predict the future. Wang Yirong, a Chinese antiquarian, was the first to realize their true worth after he found them on sale as “dragon bones” in Peking in 1903. Traditional Chinese medicine often recommended grinding up bones from the Pleistocene epoch. Although initially believed to be fakes, the bones were confirmed to be authentic nearly three decades later. Furthermore, the oracle bones stopped a lot of criticism about early Chinese history, including that from scholars who had doubted the existence of the Shang dynasty.

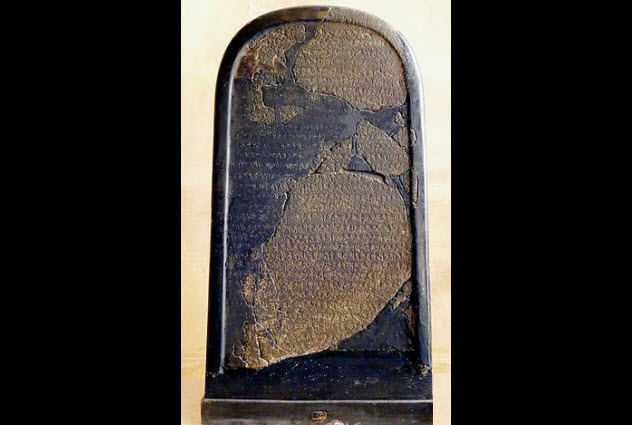

1 Mesha Stele

Language: Moabite The Mesha Stele, which contained writing with the Phoenician alphabet, was created by King Mesha of Moab after he successfully restored the lands of his people. Created around 860 BC, the stele describes the exploits of Mesha, including building projects, and the actions of Kemosh, the god of Moab, who returned to his people and helped them to throw off the yoke of Israel. In fact, the stele is the earliest nonbiblical reference that contains the word “Israel.” The first European known to have seen the stele was French missionary F.A. Klein, who was led there by a local bedouin. Klein shared the information with another Frenchman, archaeologist Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau. He recognized the importance of the find because using archaeological discoveries to prove facts within the Bible was becoming extremely popular. Clermont-Ganneau sent an Arab intermediary to take a “squeeze” (a papier-mache impression) of the stele, something which proved to be quite fortuitous. When Clermont-Ganneau sent a second person to make a stamp of it, the local bedouins, perhaps enraged by local politics or an ownership dispute, broke the stele into pieces. About 60 percent of the original stele remained. The rest was reconstructed from the squeeze procured by Clermont-Ganneau. It is now located in the Louvre.