Originally discovered through graffiti found in Pompeii in 1817, Tetraites was documented for his spirited victory over Prudes. Fighting in the murmillones style, he wielded a sword, a rectangle shield, a helmet, arm guards, and shin guards. The extent of his fame was not fully comprehended until the late twentieth century, when pottery was found as far away as France and England, which depicted Tetraites’s victories.

Not much is known about these two rivals, although their final fight was well-documented. The battle between Priscus and Verus in the first century AD was the first gladiator fight in the famous Flavian Amphitheatre. After a spirited battle that dragged on for hours, the two gladiators conceded to each other at the same time, putting down their swords out of respect for one another. The crowd roared in approval, and Emperor Titus awarded both combatants with the rudis, a small wooden sword was given to gladiators upon their retirement. Both left the theater side by side as free men.

Spiculus, another renowned gladiator of the first century AD, enjoyed a particularly close relationship with the (reportedly) evil Emperor Nero. Following Spiculus’s numerous victories, Nero awarded him with palaces, slaves, and riches beyond imagination. When Nero was overthrown in AD 68, he urged his aides to find Spiculus, as he wanted to die at the hands of the famous gladiator. But Spiculus couldn’t be found, and Nero was forced to take his own life.

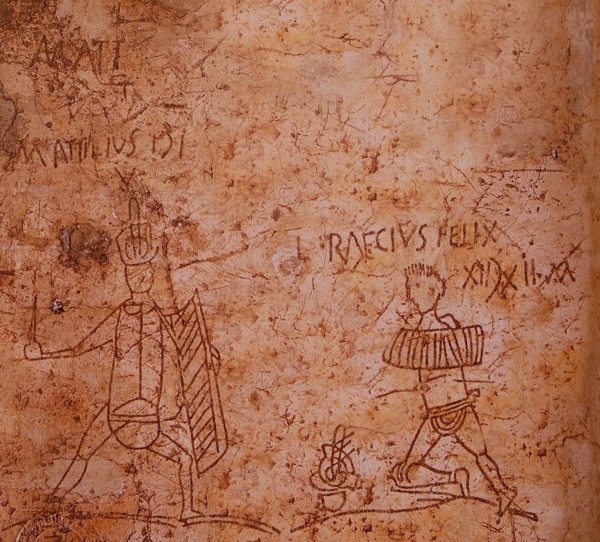

Though a Roman citizen by birth, Attilius chose to enter gladiator school in an attempt to absolve the heavy debts he had incurred during his life. In his first battle, he defeated Hilarus, a gladiator owned by Nero, who had won thirteen times in a row. Attilius then went on to defeat Raecius Felix, who had won twelve battles in a row. His feats were narrated in mosaics and graffiti discovered in 2007.

Gannicus was one of the most skilled, durable, and athletic fighters of the ancient Roman period. He could be compared to the best gladiators such as Spartacus and Crixcus due to his fighting powers and techniques. He was a Celtic gladiator, and for being so, he thrived on athleticism and a level of speed that would enable him to strike rapid and aerial assaults as well as quick jumping motions. Besides fighting preference, he had a unique appearance with tanned skin and long, messy blond hair. He also had tattoos on his body, and one of the most famous ones was a Nordic symbol that represented invincibility

Crixus, a Gallic gladiator, was the right-hand man of the number one entry on this list. He enjoyed notable success in the ring but resented his Lanista—the leader of the gladiator school and his “owner.” So, after escaping from his gladiator school, he fought in a slave rebellion, helping to defeat large armies amassed by the Roman Senate with relative ease. However, after a dispute with the rebellion leader, Crixus and his men split off from the main group, seeking to destroy Southern Italy. This maneuver diverted enemy military forces from the main group, giving them valuable time to escape. Unfortunately, the Roman legions struck Crixus down before he could exact his revenge on the people who had oppressed him for so long.

Flamma, a Syrian slave, died at the age of thirty—having fought thirty-four times and having won twenty-one of those bouts. Nine battles ended in a draw, and he was defeated just four times. Most notably, Flamma was awarded the rudis a total of four times. When the rudis was given to a gladiator, he was usually freed from his shackles and allowed to live normally among the Roman citizens. But Flamma refused the rudis, opting instead to continue fighting.

Famously played by Joaquin Phoenix in the 2000 film Gladiator, Commodus was an Emperor who enjoyed battling gladiators as often as possible. A narcissistic egomaniac, Commodus saw himself as the greatest and most important man in the world. He believed himself to be Hercules—even going so far as to don a leopard skin like that famously worn by the mythological hero. But in the arena, Commodus usually fought against gladiators who were armed with wooden swords and slaughtered wild animals that were tethered or injured. As you could guess, most Romans, therefore, did not support Commodus. His antics in the arena were seen as disrespectful, and his predictable victories made for a poor show. In some instances, he captured disabled Roman citizens and slaughtered them in the arena. As a testament to his narcissism, Commodus charged one million sesterces for every appearance—although he was never exactly “invited” to appear in the arena. Commodus was assassinated in AD 192, and it is believed that his actions as a “gladiator” encouraged his inner-circle to carry out the assassination.

By far the most famous gladiator in history, Spartacus was a Thracian soldier who had been captured and sold into slavery. Lentulus Batiatus of Capua must have recognized his potential, for he purchased him intending to turn him into a gladiator. But a warrior’s fierce independence is not easily given up: in 73 BC, Spartacus persuaded seventy of his fellow gladiators—Crixus included—to rebel against Batiatus. This revolt left their former owner murdered in the process, and the gladiators escaped to the slopes of nearby Mount Vesuvius. While in transit, the group set free many other slaves—thereby amassing a large and powerful following. The gladiators spent the winter of 72 BC training the newly freed slaves in preparation for what is now known as the Third Serville War, as their ranks swelled to as many as 70,000 individuals. Whole legions were sent to kill Spartacus, but these were easily defeated by the fighting spirit and experience of the gladiators. In 71 BC, Marcus Licinius Crassus amassed 50,000 well-trained Roman soldiers to pursue and defeat Spartacus. Crassus trapped Spartacus in Southern Italy, routing his forces and killing Spartacus in the process. Six thousand of his followers were captured and crucified, their bodies made to line the road from Capua to Rome.