The names of some people on this list may come as a surprise, for it’s hard to believe they could have stomached the anguish of the executed, who fell to their deaths at the end of ropes around their necks or lost their heads to swords or other instruments of death. It’s also hard to believe the executions some of these writers witnessed inspired scenes in their own classic literary works.

10 Dante Alighieri

Italian poet Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) not only saw convicted criminals burned alive, but he also witnessed the executions of assassins who were buried headfirst in the ground, “with only their legs protruding.” The dreadful spectacle inspired Dante’s portrayal of a similar fate for the unrepentant sinners of his Inferno, whose legs stick “out of holes in a rock.” In the poem, “he bends to talk to one of them,” as if he were a priest hearing “the last words of a condemned man” who prolongs his confession to postpone “the terrible moment when the earth is shoveled in and smothers him.”[1]

9 Samuel Pepys

Among a crowd of 12,000 to 14,000 spectators, English diarist Samuel Pepys (1633–1703) watched the 1664 hanging of convicted burglar James Turner. To better observe the execution, Pepys paid a shilling to stand on a cart wheel, thus spending an hour “in great pain,” while Turner delayed the inevitable with “long discourses and prayers,” hoping for a reprieve that didn’t come. After the hanging, Pepys returned home, “all in a sweat,” to dine alone, before eating a second dinner with friends at the Old James tavern. This wasn’t the first execution Pepys had witnessed. On October 13, 1660, he’d attended Major-General Harrison’s execution. Not only was the regicide to be hanged, but Harrison had also been sentenced to be drawn (that is, to have his abdomen cut open and his entrails withdrawn) and quartered (to be beheaded and have his body cut into four pieces). After Harrison’s body was “cut down, his head and heart [were] shown to the people,” who responded with “great shouts of joy.” In 1649, Pepys added, he’d had the opportunity to witness the beheading of King Charles at White Hall, the main residence of British monarchs at the time, so he could now boast of having seen “the first blood shed in revenge for the blood of the King at Charing Cross.”[2]

8 James Boswell

Scottish lawyer and biographer James Boswell (1740–1795) seems to have been obsessed with witnessing public executions. He attended several. One was that of William Harris, a client sentenced to death for forgery. On the eve of Harris’s execution, Boswell visited him. The next day, May 30, 1770, he attended the condemned man’s execution, which, Boswell wrote, left him “much shocked and still gloomy.” The next year, on September 25, Boswell apparently witnessed the execution of convicted robber William Pickford, writing on October 20, 1771, to his friend John Johnston that he’d last seen Pickford “at the foot of the gallows.” On March 24, 1773, after attending some of the trial of Alexander Madison and John Miller, who were convicted of stealing sheep, Boswell attended their hangings. They were executed alongside John Watson, who’d been sentenced to death for breaking into a house. Boswell found the “effect diminished as each one went.” Boswell’s defense of another client, Margaret Adams, was unsuccessful. She and her younger sister Agnes were being tried for murder, and Boswell convinced the court that the siblings should be tried separately. Agnes was “later reprieved,” but Boswell’s brief note concerning his whereabouts on March 2, 1774, “at M. A.’s execution,” indicates his client wasn’t as fortunate. On September 21, 1774, Boswell witnessed the execution of sheep thief John Reid. Then, Boswell attended the April 19, 1779, execution of James Hackman, who’d been sentenced to death for murdering Martha Ray. The execution occasioned both Boswell’s “account of the trial and a letter of reflection on Hackman’s fate for the St. James’s Chronicle.” Next, Boswell attended a series of mass executions. On June 23, 1784, he observed “the shocking sight of fifteen men executed before Newgate,” before attending the executions of 19 more men at the same prison a year later. On July 1, 1785, he saw ten more men die at Newgate. Five days later, accompanied by Sir Joshua Reynolds, Boswell went to see Edmund Burke’s former servant Peter Shaw executed for arson, alongside four other condemned men, writing about the affair for the Public Advertiser. The same year, on August 16 and 17, he watched “seven men and a woman, including siblings Elizabeth and Martin Taylor,” executed for burglary, interviewing some of the condemned men beforehand and publishing an article concerning the event in the Public Advertiser. He also interviewed murderers Thomas Masters and Antonio Marini on April 19, 1790, before their executions.[3] Boswell confessed he was “never absent from a public execution,” explaining that his initial shock and feelings of “pity and terror” gradually gave way to “great composure.” He was motivated to witness executions, he said, because of his great curiosity about death.

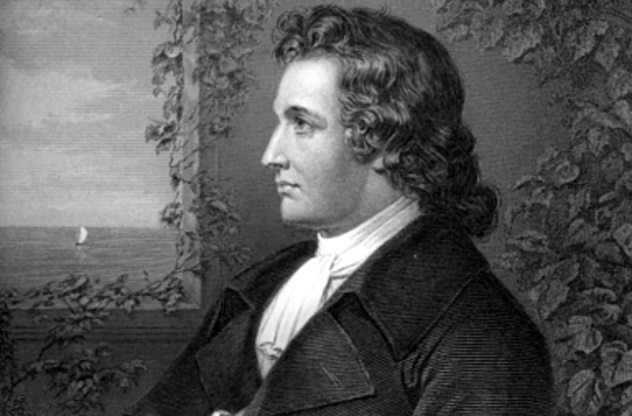

7 Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe

On January 14, 1772, in Frankfort, Germany, Susanna Margarethe Brandt, 25, was beheaded. She’d been drugged and raped, and when she delivered the resulting infant, she murdered it, claiming she’d been under the influence of a demonic power. German dramatist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) may have witnessed her execution. If so, the event may have inspired Gretchen, the character who commits infanticide in his two-part tragedy, Faust. Several parallels between Gretchen and Brandt suggest the former might have inspired the latter. Brandt claimed the rapist had spiked her wine; Gretchen poisoned her mother with wine. Both Brandt and Gretchen blamed their actions on the Devil, and both had a brother in the army. Brandt’s sister reassured her that she hadn’t been the first woman ever to have been seduced, and Mephisto told Gretchen the same thing, using the same words Brandt’s sister used to console her: “You are not the first.”[4]

6 Lord Byron

The English Romantic poet Lord Byron (1788–1824) described a progression of emotion similar to that which Boswell experienced. While he was visiting Rome, Byron attended the beheadings of three condemned men. “The first,” he wrote, “turned me quite hot and thirsty, and made me shake so that I could hardly hold the opera glass; the second and third (which show how dreadfully soon things grow indifferent), I am ashamed to say, had no effect on me as a horror.”[5]

5 Hans Christian Andersen

In his autobiography Danish fairy tale author Hans Christian Andersen (1805–1875) recounts having witnessed the public execution of a man in 1823, after which a father collected “a cup of the dead man’s blood” to give to his epileptic offspring to drink, hoping the vital fluid would cure the child. It appears the father’s belief was rooted in superstitions concerning the curative effect of blood. Since ancient days, it was believed that blood could restore health. It was thought that the blood of people who died violently or were executed could cure all manner of sicknesses and diseases because blood, the “elixir of life,” contained “soul-essence,” imbuing those who drank it with energy and strength.[6]

4 William Makepeace Thackeray

The British novelist William Makepeace Thackeray (1811–1863) tells how “Dash,” whom he described as “one of the most eminent wits in London,” had kept those who planned to attend the execution of Francois Courvoisier in stitches during their wait the night before at a club, joking about “the coming event.” Thackeray admitted he and his companions found murder “a great inspirer of jokes.” After hours of waiting, Courvoisier “bore his punishment like a man”: “His arms were tied in front of him. He opened his hands in a helpless kind of way, and clasped them once or twice together. He turned his head here and there, and looked about him for an instant with a wild imploring look. His mouth was contracted in to a sort of pitiful smile. He went and placed himself at once under the beam.” When a “night-cap” was pulled over the condemned man’s head and face, Thackeray shut his eyes, and the trapdoor was sprung, Courvoisier dropping to the end of his rope. Thackeray was haunted by the execution; 14 days later, he continued to see “the man’s face continually before [his] eyes.”[7]

3 Charles Dickens

On November 13, 1849, English novelist Charles Dickens (1812–1870) attended the public execution of Frederick and Maria Manning. The husband and wife were executed at the Horsemonger Lane Gaol for the murder of their friend, whose body they then buried beneath the kitchen floor. Their motive in murdering the man was robbery; they’d valued their victim’s money more than they’d valued his life. A husband and wife hadn’t been executed together for 150 years, and the occasion was advertised as the “Hanging of the Century.” Part of a crowd of 30,000 witnesses, Dickens watched the hanging from the comfort of an upstairs apartment he’d rented near the prison. Despite his own presence at the execution, the author denounced the public spectacle in a “scathing” letter to The Times newspaper, condemning the carnival-like air of the affair. In his letter, Dickens claimed he’d attended the execution not to see the couple hanged, but to observe the crowd, which he described in some detail, as “thieves, low prostitutes, ruffians, and vagabonds of every kind” whose “foul behavior” in jeering at the condemned and exhibiting shameless and “brutal mirth” made him ashamed to be among their number.[8] Despite his professed revulsion by such spectacles, this wasn’t the first time Dickens had attended a public execution. On July 6, 1840, the novelist had been part of the crowd observing the execution of Courvoisier at Newgate Prison in London, England, attending the affair with Thackeray and Dash. The condemned man had been found guilty of having cut Lord William Russell’s throat as Russell lay in bed. Dickens wrote of his disgust for the “odious” crowd, which exhibited “no sorrow, no salutary terror, no abhorrence, no seriousness,” showing, instead, “ribaldry, debauchery, levity, drunkenness and flaunting vice in 50 other shapes.”

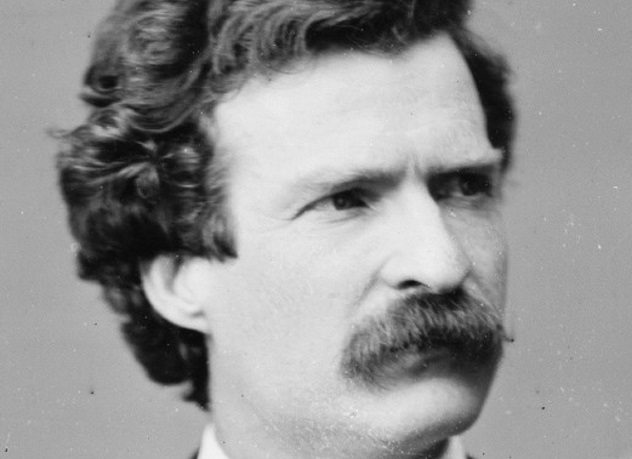

2 Mark Twain

American novelist and humorist Mark Twain (1835–1910), was haunted by his memory of the hanging he’d attended in Nevada during the latter half of the 19th century. In recounting the experience for a Chicago newspaper, he wrote, “I can see that straight stiff corpse hanging there yet, with its black pillow-cased head turned rigidly to one side, and the purple streaks creeping through the hands and driving the fleshly hue of life before them. Ugh!” Twain was writing of the April 28, 1868, execution of Frenchman John Milleain (referred to by Twain as “John Melanie”), who’d been caught selling one of the dresses of his victim, Julia Bulette, whom he’d murdered in January 1867 before ransacking her parlor. An immigrant, Milleain spoke little English and was easily convicted of the crime, although he insisted he was innocent right up to the moment the trapdoor was sprung. Twain described the hanging in a letter he sent from Virginia City, which was published in the Chicago Republican on May 31, 1868. The condemned man went courageously to his death, Twain wrote. It was only at the end of the rope that “a dreadful shiver started at the shoulders, violently convulsed the whole body all the way down, and died away with a tense drawing of the toes downward, like a doubled fist,” until “all was over.”[9]

1 Thomas Hardy

English novelist Thomas Hardy (1840–1928) was just 16 years old when he witnessed a hanging, climbing a tree near the gallows to gain a good vantage point. Elizabeth Martha Browne, 45, had been convicted of murdering her husband, and now, outside Dorchester Gaol at 9:00 AM on August 9, 1856, she was being made to pay for the crime with her own life. By the century’s end, the town of Dorchester had a population of 9,000, and almost half a century before that year, a crowd numbering between 3,000 and 4,000 people had gathered to witness the spectacle. Decades later, Hardy described the condemned woman as showing “a fine figure . . . against the sky as she hung in the misty rain,” her “tight black silk gown” emphasizing “her shape as she wheeled half round and back” at the end of her rope. It’s been suggested that Browne’s death may have struck an erotic chord in the teenager, who may have been fascinated by “her writhing body in the tight dress and [by her] facial features partially visible through the rain soaked hood.” In any case, the horrific incident so affected Hardy it inspired his famous 1891 novel Tess of the D’Urbervilles.[10]