10Martin Guerre

The Middle Ages were an easy era for identity thieves. When identification documents didn’t exist and very few people could read or write, the very idea of self-identity was fluid at best. This might help to explain the ridiculous exploits of Arnaud du Tilh. On a summer afternoon in 1556, Arnaud waltzed into the Basque town of Hendaye and proclaimed that he was the long-lost Martin Guerre. The real Guerre had disappeared to join the Spanish army eight years earlier, abandoning his young wife Bertrande, and hadn’t been heard from since. Surprisingly, Bertrande appeared to believe the imposter’s story, welcoming the new “Martin” with open arms. The rest of the townsfolk were apparently convinced as well—in the days before photographs, most people were a little uncertain about what Martin had looked like to begin with. For the next three years, Bertrande lived a happy life with her returned husband, whom she noted was much kinder than the first incarnation of Martin. However, holes soon appeared in the new Martin’s story—for starters, he had apparently forgotten how to speak Basque. He also seemed to have lost his love of athletics, and his children looked nothing like him. Furthermore, he planned to sell his ancestral land, which was an unthinkable action for a proud Basque. Soon, Martin’s uncle accused him of being a fraud and brought a suit before the regional court. The first proceeding agreed that “Martin” was an imposter—but he was acquitted on appeal and nearly walked off scot-free. Until, in one of legal history’s great dramatic moments, the real Martin Guerre hobbled up with a wooden leg and immediately proved Arnaud du Tilh a fake. Arnaud was condemned to death, and Bertrande was left looking rather silly.

9Lobsang Rampa

Of all the unlikely tales, it might be thought that no one would believe an Irish plumber who suddenly claimed to be inhabited by the spirit of a dead Tibetan lama. But “Lobsang Rampa,” aka Cyril Hoskins, still sells thousands of books every year based on his outlandish story. In the mid-1950s, Hoskins came out of nowhere to publish the best-selling novel The Third Eye, which detailed his former life as the lama Lobsang Rampa. Hoskins apparently realized he was Rampa after he hit his head falling out of a tree. The Third Eye was filled with such absurd claims as the existence of Yetis, lamas who flew around on magical kites, and the geologically surprising revelation that the Himalayas were formed when another planet collided with the Earth. Perhaps most incredibly, Hoskins claimed to have undergone an actual physical medical procedure to install a “third eye” in the middle of his forehead. Conveniently, Hoskins “forgot” how to speak Tibetan and would fall on the ground screaming whenever anyone asked about it. The Buddhist scholar Agehananda Bharati reviewed Hoskins’ work quite succinctly: “The first two pages convinced me the writer was not a Tibetan, the next 10 that he had never been either in Tibet or India, and that he knew absolutely nothing about Buddhism of any form, Tibetan or other.” Anthropologists repeatedly exposed “Lobsang” as a fraud, and he never countered any of their accusations. His books still sold tens of thousands of copies. Indeed, The Third Eye and its follow-ups were instrumental in popularizing Buddhism in the West. Unfortunately, they were also instrumental in connecting the religion with crystal balls and other New Age nonsense, which continues to color its perception in some circles to this day.

8Tile Kolup

If at first no one believes you are the dead Holy Roman Emperor, try and try again. Such was the motto of Tile Kolup, who first declared himself Frederick II in the German city of Cologne in 1284. By that point, Frederick, who had quite certainly died in 1250, would have been over 90 years old. As a result, the unamused citizens of Cologne threw Kolup into a sewer and then chased him out of town. Undeterred, Kolup decided to try his luck in nearby Neuss, where the citizens apparently weren’t quite as sharp—Kolup was rapturously received and hailed as Frederick II. Kolup’s success was based on his vast education, which allowed him to forge imperial documents with relative ease. He also made use of the popular “King in the Mountain” legend, which stated that past heroes would enter a magical sleep in some hidden place, returning when their country needed them most. Additionally, many were astonished by Kolup’s apparent foresight, since he seemed to know in advance the names of all he met. These simple tricks convinced many that he was truly Frederick II, and for a few months Kolup presided over an imperial court at Neuss. He even had coins minted in his honor. Of course, the true Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf, was less than amused by the whole thing. When he arrived to attack the imposter’s court, Kolup’s followers suddenly realized that he probably wasn’t the 95-year-old Frederick in a 30-year-old’s body. Kolup was then unceremoniously declared a heretic and burned at the stake, ending a fairly embarrassing period in German history.

7Yemelyan Pugachev

Throughout history, perhaps no country has proven quite as gullible as Russia, which was actually briefly ruled by a man claiming to be Ivan the Terrible’s long-dead son Dmitri. No sooner had that imposter been dethroned than two other Dmitris popped up. Then, in the 1760s, no less than seven people claimed to be Tsar Peter III reborn. Unlike the Dmitris, only the seventh false Peter, an illiterate Cossack named Yemelyan Pugachev, achieved mainstream success. Pugachev was an athletic, dark-faced man with a flowing black beard, who bore almost no physical resemblance to the real Peter. Another obstacle was the widespread knowledge that Peter had been murdered in 1762, 11 years before Pugachev began his rebellion. But the facts never mattered too much in Russia. The Cossacks in particular resented the regime of Peter’s wife, Catherine the Great, who had repealed much of her husband’s pro-serf legislation. Catherine had even gone so far as to tax the serfs for growing a beard, which understandably upset the independent-minded Cossacks. In September 1773, Pugachev issued a manifesto calling all Cossacks and Tatars to join him, the rightful Tsar Peter III, in reclaiming his throne. An army of thousands flocked to Pugachev’s charismatic leadership, allowing him to overrun the Volga River region. The rebellion’s early success was aided by the concentration of Russian forces on the border with the Ottoman Empire. For two years, Pugachev’s troops rampaged along the Volga, even sacking the metropolis of Kazan. But once the Ottoman situation was resolved, Catherine was able to bring her full military might to bear against her alleged husband. The rebellion was quickly crushed, and Pugachev was sent to Moscow in a cage. It wasn’t quite the end of his legacy—he was later immortalized in Pushkin’s romantic novel The Captain’s Daughter.

6Iron Eyes Cody

In the early 1970s, the environmental movement scored a huge hit with the influential “Crying Indian” ad campaign. In the famous PSA, a Native American man, played by Iron Eyes Cody, sheds a single, dramatic tear at the sight of the pollution destroying his ancestral home. The moving ad jumpstarted national recycling programs, as many Americans were jolted into a greater awareness of the natural world. Iron Eyes Cody, who represented himself as the son of a Cree mother and a Cherokee father, went on to play Native Americans in dozens of ads, movies, and television shows. But Cody had a secret—his birth name was Espera Oscar de Corti and he was 100 percent Italian. Cody was so dedicated to his role that he was never seen without a braided wig, headdress, and moccasins, and eventually married a Native American woman. Of course, Cody’s entire birth town of Kaplan, Louisiana knew that Iron Eyes was a purebred Italian. But they were too proud of their homegrown star to say anything and Iron Eyes continued playing Native American parts until his death. His image is said to have been viewed over 14 billion times, which would make him by far the most viewed Native American in all of history—if only he was actually Native American.

5Nadezhda Durova

When some people are bored they take up guitar, or get married, but Nadezhda Durova decided to join the Cossacks and fight Napoleon. There was just one problem—Durova was female, and Russia was even less progressive in the Napoleonic Era than it is today (read: not at all). So Durova disguised herself as a man and somehow managed to convince her superiors that she was a Russian nobleman who had defied his family to join the military. Which actually couldn’t have been farther from the truth, since Durova’s father was a general who had brought her along on all his campaigns. At the age of four, Durova was thrown from a moving carriage and almost given up for dead. Such hardships created the sort of woman who could convincingly join the Cossacks. In her first engagement against the French, Durova joined in with every assault because she couldn’t stand sitting around. Such bravery brought her to the attention of Tsar Alexander I, who apparently saw through her thin disguise immediately. He told her to go home, but Durova convinced him to let her continue serving, which she did until Napoleon was soundly defeated in 1815. Her femininity prevented her from being promoted, but somehow her eternally youthful appearance never fully blew her cover and she retired a well-regarded soldier in the Russian military.

4Bampfylde Moore Carew

Born into an aristocratic British family, Bampfylde Moore Carew decided to spend his life pretending to be an impoverished gypsy instead. At a young age, he ran away to join a band of travelers and was soon dubbed “King of the Beggars.” After a taste of the wandering life, Carew became notorious for pretending to be a different person almost every day. Sometimes he was a clergyman, or a seaman, a ratcatcher, a lunatic, or even an old woman. He even used his disguises to beg for money from other aristocrats near his birthplace, who should certainly have recognized him. Another of Carew’s tactics was to scour the newspapers for the latest natural disaster and pretend to be someone afflicted by it. Even being caught and sent to America as a prisoner didn’t faze him—he simply escaped right back to England. Twice. Near the end of his life, Carew joined the Jacobite army of Bonnie Prince Charles, before abandoning the rebels as their cause fell apart. In 1745, he published his popular autobiography: The Life and Times of Bampfylde Moore Carew, which made him famous throughout the British Empire. Of course, Carew’s exploits should be taken with a mountain of salt, since his memoirs are our only source for many of them. For all we know he could have been a provincial salt salesman. But that’s no fun.

3Carlos Castaneda

Like Lobsang Lampa, Carlos Castaneda deceived gullible hippies with a psychedelic tale that proved too good to be true. In 1968, Castaneda published The Teachings of Don Juan, which quickly became wildly popular with the New Age movement. The book detailed Castaneda’s encounters with a Yaqui Native American shaman named Don Juan, who took him on magical adventures with the help of peyote and mescaline. These psychedelic substances allowed Castaneda to converse with lizards, speak to Mescalito (the spirit which lives in all peyote plants), and take on an animal body. So far, the story seems airtight, but there were a few problems. For starters, no one else ever met Don Juan, the Yaqui don’t use peyote or mescaline, and Castaneda somehow never learned any Yaqui words in all his years with Don Juan. As a result, most anthropologists came to consider the author an outright fraud. An illuminating anecdote tells of how one of Castaneda’s friends happened to mention that Buddha and Jesus never wrote anything down themselves—their disciples recorded their teachings and could have changed whatever they wanted. According to Castenada’s friend, the author grew very quiet upon hearing this and began writing The Teachings of Don Juan shortly afterward. Not that Castaneda’s career suffered from these revelations—as of today, he has sold nearly 28 million books worldwide. Further books detailed even more adventures with Don Juan, who eventually went up to heaven in a ball of fire (making it even more difficult for anyone to meet him). Later, Castaneda created a cult based on his Tensegrity theory. Supposedly derived from ancient Toltec shamans, Tensegrity involves glowing eggs, spiritual exercises, and, of course, a large cabal of women for Castaneda to be intimate with.

2Perkin Warbeck

Poor Henry VII of England could never catch a break. No sooner had he defeated Lambert Simnel, who claimed to be the murdered Edward VI, than another imposter popped up claiming to be Edward’s brother, Richard of Shrewsbury. In truth, both Edward and Richard were most likely murdered in the Tower of London by Richard III, but the uncertain nature of their fates left plenty of opportunities for imposters. That said, few should have believed Perkin Warbeck was Richard, mainly because Warbeck was born in Belgium and barely spoke English. But he did bear some resemblance to the real Richard and various enemies of Henry decided to just go with it. As a result, Warbeck eventually gained the support of France, Scotland, and the Holy Roman Empire—he was even invited to the funeral of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian. However, Warbeck was not a natural leader, or even a brave man. In 1495, he attempted to invade England, but didn’t even leave his ship while his soldiers were slaughtered on the shore. Later, Warbeck lived in Scotland, where King James IV assisted him in another failed invasion. When that fell apart, he went to Ireland, where he gathered a few thousand men. An invasion of England in 1499 was quickly defeated and Warbeck spent the rest of his life in the Tower of London, where the real Richard of Shrewsbury had actually died.

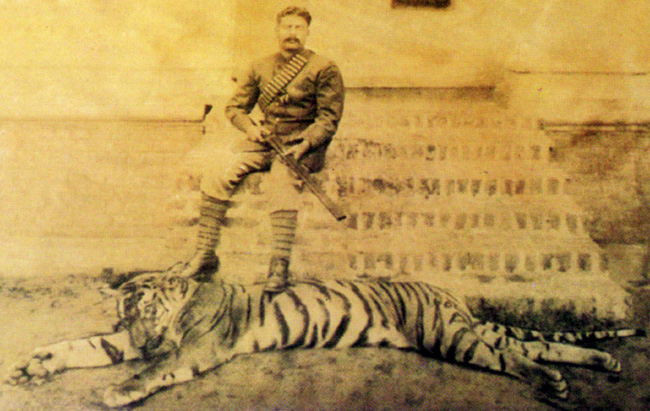

1The Bhawal Case

In 1911, the heir to the Bhawal estate, Ramendra Narayan Roy, the dissolute, tiger-hunting Prince of Bhawal, died under mysterious circumstances. Almost immediately, rumors began to circulate that he still roamed the countryside. But nothing came of the stories until 1920, when a half-naked mystic showed up and sat in front of the Bhawal estate. For nearly a month, the mystic said nothing, but eventually he declared himself the missing heir. He explained that some of his cousins had attempted to poison him because he had syphilis, but the poison had failed to kill him, and then a freak hailstorm stopped his cremation. After the botched murder attempt, he had escaped to become a wandering ascetic and completely forgotten his past life. Only in 1920 did he suddenly remember his true identity and return to claim the Bhawal estate. A completely believable tale. Some, but not all, of the Bhawal family actually believed his story, examining his body to find the same “marks” as the original Ramendra. Eventually, they declared him the true heir and gave him much of the Bhawal estate. Naturally, this angered those relatives who were not so easily duped by a wandering, forgetful beggar-priest, and they sued the new heir. The court case dragged on for 20 years and, against all the odds, the imposter won in 1945. However, in a moment of cosmic irony, he died on the way to offer a sacrifice for his undeserved victory. Geoff gained seven worthless liberal arts degrees. Follow him on Twitter to see how that’s going (spoiler: not well).