For those in the West, Chinese history is either completely unknown or only vaguely identified. However, in many mandatory Western civilization courses, professors like to joke that Western history is a string of endless wars and genocides. When you get those same professors in private, they will readily admit that Eastern civilization is no different, especially when it comes to China. In those thousands of years of civilization, China has been the scene of several genocidal bloodbaths. Some of these were due to outside invasions, while others were the result of civil wars and imperial politicking. Either way, the following incidents featured mass slaughter on a scale unprecedented until the horrors of World War II. Some even exceeded the body count of the Bolsheviks, Joseph Stalin, and Adolf Hitler.

10 January 28 Incident

Long before Hitler’s tanks rumbled across the border into Poland, Japanese soldiers, ships, and planes were pressing in on China. At that time, China was hardly in a position to defend itself. Following the revolution of 1911–12, the former Qing Empire had become a fractured state controlled by several different warlords. Even after the successful Northern Expedition of 1927, the Kuomintang Party and its National Revolutionary Army (NRA) only had a tentative hold on the coast. Making matters worse was the fact that following the Kuomintang takeover of Shanghai, the violent assaults against the communists led to the Chinese Civil War, which would not end until Mao’s takeover of power in 1949. The power in the best position to exploit this situation was Japan. The Japanese Empire had been expanding into Manchuria since 1895 when, following the Japanese victory over the Qing, Japan won certain rights in the region. The Kwantung Army, which had been established in Manchuria following Japan’s defeat of the Russian Empire in 1905, wanted more Chinese land. The Kwantung Army was virtually independent of Tokyo and full of junior officers who belonged to the “Imperial Way” faction. They believed in overthrowing parliamentary politics in Japan to create a vast Japanese empire ruled by an autocratic emperor. In September 1931, a bombing on a Japanese-owned railroad provided the excuse needed by the Kwantung Army to occupy all of Manchuria and claim it for the new pro-Japanese state known later as Manchukuo. On January 28, 1932, another “incident” brought Japan and the Kuomintang to the brink of open hostilities. Following the Kwantung’s takeover of Manchuria, Chinese citizens began a boycott of all Japanese goods. In response, Japanese soldiers and sailors were deployed to Shanghai, the most important port in Asia and the biggest city in China, to ostensibly protect Japanese lives and property. At dawn on the 28th, the Japanese ship Notoro launched seaplanes that dropped flares all across Shanghai to obscure a landing of the elite Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF). The SNLF soon began skirmishing with the NRA’s 19th Route Army. The following day, even more seaplanes flew over Shanghai. They were ordered to bomb military targets. However, due to poor weather, the Japanese planes bombed mostly civilian targets. Respected historian Barbara Tuchman would later describe this event as the world’s first “terror bombing,” which means that Tuchman believed that the Japanese seaplanes deliberately targeted Shanghainese civilians. Tuchman and other scholars have put the death toll at 10,000–20,000 Chinese civilians. Other historians have cast doubt on these figures. They have noted that the seaplanes used during the battle, the E1Y, only carried 200 kilograms (441 lb) of bombs and had a lone 7.7mm machine gun, thus making it hard to believe that they could do that level of damage. Whatever the true cost, no one questions that thousands of Shanghainese civilians died during the undeclared war in Shanghai. Japanese raids into Shanghai occurred until February, but the SNLF kept getting bogged down by the surprisingly determined 19th Route Army. However, it was all over on March 1, 1932, when the SNLF defeated their Chinese foes. A ceasefire was declared, Shanghai was demilitarized (except for Japanese and Western forces), and Manchukuo was secured.[1]

9 Dzungar Genocide

Few parts of today’s China have seen as much bloodshed as the far western province of Xinjiang. Today, the province is the home of state-run concentration camps designed to purge the Muslim Uighur majority of their religion. Beijing is also using a “soft genocide” of demographic replacement to make Xinjiang less Muslim and less Turkic and more Han Chinese. Already, by 2010, Uighurs were less than 50 percent of the total population, while the Han Chinese population had grown considerably since the 1990s. The Chinese state, even when it was not controlled by the ethnic Han, has always sought to bring Xinjiang to heel. This was done not only to expand imperial control and increase tax revenue but also to deny Russia another Central Asian possession. In the 17th century, the biggest power in Xinjiang was the Dzungar Khanate, a state ruled by a federation of nomadic Mongol tribes. At the khanate’s height, the Dzungar warlords reached trade agreements with Russia, made an alliance with the Dalai Lama in Tibet, and instituted a law code (“Great Code of the Forty and the Four”) that only applied to ethnic Mongols. The Buddhist Dzungars began to irk the Qing dynasty when they invaded Tibet in 1717, which required a Qing army to respond. In 1720, Qing Emperor Kangxi sent a large expedition to expel the remaining Dzungars from Tibet. The Tibetans greeted the Qing as saviors, while the Qing installed Kelzang Gyatso as the seventh Dalai Lama. Fearful that the Dzungars would ride again into either Tibet or one of the isolated Qing provinces in the west, the Qianlong emperor sent numerous military expeditions into Dzungar territory in the hopes of conquering the khanate. This was achieved in 1757 thanks to a combined army of Manchu and Mongol horsemen. Prince Amursana, the last Dzungar prince, found refuge in Russia. The Qing conquest and pacification of the Dzungar Khanate wiped out 80 percent of the total Dzungar population. That amounted to a death toll between 480,000 and 500,000. The remaining 20 percent of the Dzungars were forced into slavery, while the lands of the former khanate were settled by Manchu, Mongol, and Han migrants.[2]

8 Warlord Civil Wars

As already mentioned, the Warlord Period was a time of great instability in China. It was also a time of endless warfare, with warlord “cliques” battling each other constantly to gain money, land, and prestige. These wars include the Zhili-Anhui War of 1920, which pitted the Zhili Clique of Hebei Province against the Anhui Clique of Anhui Province. This was the first of the warlord wars and began when the Anhui attacked the Zhili on July 14, 1920. The whole purpose of this was to grab control of the government in Beiyang (Beijing). Despite receiving support from the Japanese Army, the Anhui would eventually fall to the combined Zhili and Fengtian forces that captured Beijing on July 19. In total, approximately 35,000 soldiers died in this war. Following their short-lived truce, the Zhili and Fengtian cliques fought each other in 1922 and 1924. The Fengtian forces, based in what is today Liaoning Province, won the second war thanks to support from the Japanese as well as White Russian mercenaries commanded by Konstantin Petrovich Nechaev. The Zhili-Fengtian conflicts killed tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands. A later conflict known as the Anti-Fengtian War saw the early incarnation of the Kuomintang try to overthrow the Fengtian government in Beijing with Soviet support. The Fengtian Clique—with material, financial, and military support from Japan, White Russian volunteers, and the Zhili Clique—managed to win the war. The war, which lasted from 1926 until 1927, only served to weaken the battle-weary warlord armies and increase distrust among the Chinese population. Also not helping the warlord cause were the warlords themselves. While some proved to be excellent administrators (the best example was Yan Xishan of the Kuomintang), most were cynical brutes who made money by exploiting misery. Most warlords had been bandits before becoming soldiers, and thus criminal operations were natural to them. Feng Yuxiang, the “Christian Warlord,” publicly denounced narcotics while simultaneously making a yearly income of $20 million in opium-related taxes. Muslim warlord Ma Hongkui of Ningxia Province was one of China’s greatest generals but also a tyrant. After becoming governor of Ningxia in 1932, Ma reportedly carried out one execution a day. One of his first moves as governor was to decapitate 300 bandits. Ma’s strong anti-communism also meant that communists and suspected communists in Ningxia often wound up dead. However, the most colorful and vile warlord general was Zhang Zongchang (aka the “Dogmeat General”). Based in the wealthy coastal province of Shandong, Zhang’s army, like all armies in China (including the Nationalists), made money from opium and forcing captured women into prostitution. However, Zhang excelled at this trade and was dubbed China’s “basest warlord” by Time magazine. Zhang was notoriously lecherous. During the height of his power, he had 30–50 concubines who hailed from China, Korea, Japan, Russia, France, and the United States. Besides being a playboy who constantly bragged about the size of his penis as well as being a known gambler and opium addict, Zhang was a poet whose most famous piece of doggerel ends with the line, “Then I’ll have my cannons bombard your mom.”[3]

7 Panthay Rebellion

China’s current war against Islamist insurgents is nothing new. Way back in the days of the Manchu Qing dynasty, Beijing constantly found itself at war with Muslim armies, which originated both from within China and outside of China’s borders. Between 1856 and 1873, a large Hui Muslim revolt in Yunnan Province required the Qing to put down the insurgency with force. According to historian David G. Atwill, the traditional explanation that the revolt came about because of Hui Muslim hatred of the Han Chinese is not totally true. Rather, what the Chinese know as the Rebellion of Du Wenxiu began as a socioeconomic protest against Qing meddling. In particular, between 1775 and 1850, Han Chinese migration to Yunnan saw the province’s population increase from 4 million to 10 million. This migration caused a sharp culture clash between the Han and Hui and led to environmental deterioration and an unsuccessful Qing attempt to establish direct imperial control over Yunnan.[4] According to Atwill, the rebellion began when Han Chinese societies and Han Chinese landowners began targeting Hui citizens during well-coordinated riots in the cities. Muslim leaders Ma Dexin, Ma Rulong, and Du Wenxin formed militias to avenge the Muslim deaths during these riots. But their armies later became multiethnic movements aimed at fighting against the Qing government. Du (aka Sultan Sulayman) became the rallying point for an independence movement. Du received weapons and encouragement from British Indian officials in Burma, while the Qing received support from French officials in Tonkin. The Qing defeated the rebellion and cruelly punished the rebels. Millions of Hui Muslims and other Yunnanese immigrants flooded into the Shan State of British Burma. Many of these immigrants would later become the movers and shakers of the region’s drug trade. Those rebels who did not surrender to the Qing were put to death. All told, approximately one million Hui Muslim and non-Muslim rebels and civilians died. The Qing lost one million as well.

6 Dungan Revolt

While the Muslims of Yunnan Province were in revolt, the Muslims of the central and western provinces of Shaanxi, Gansu, Ningxia, and Xinjiang were also in open rebellion against the Qing. Between 1862 and 1877, Qing armies, Han Chinese locals, and Muslims of every background went to war with each other all across China. Tragically, the cause of the war was downright stupid. Sometime in 1862, an argument began between a Han merchant and a Hui Muslim buyer of bamboo poles. When the Hui customer refused to pay the entire price asked by the merchant, the two ethnic groups began fighting one another. What happened in the immediate aftermath is unclear, but in that year, the Hui people on the western bank of the Yellow River in the Shaanxi, Gansu, and Ningxia provinces declared an independent Muslim state. At the same time, the Turkic Muslims of Xinjiang broke out in rebellion against Beijing. In 1864, the province’s capital of Urumqi was in rebel hands. As with every conflict during the late Qing Empire, the Dungan Revolt was international. The Qing government received support from Hui loyalists as well as the Khufiyya Sufis. The Hui Muslims of the central plains were alone and very disorganized. Meanwhile, the Xinjiang cause and its leader, Yaqub Beg, received support from Russia, the British Empire, and the Ottoman Empire. Yaqub Beg was responsible for turning the revolt into a tripartite war when, in the 1860s, the Turkic Muslims declared war on Han Chinese settlers and “jihad” against the Hui Muslims (Dungans). The war had few set battles, but this did not stop the Dungan Revolt from becoming one of history’s most genocidal conflicts. By 1877, in Shaanxi, Gansu, and Ningxia, two million Hui Muslims were dead while roughly six million Han had also been killed. These deaths represented almost 50 percent of the entire population of the three provinces. It took the Qing Army two years to retake Xinjiang. When they did, millions of Hui Muslims fled to Russia while the Uighur, Uzbek, and Afghan soldiers of Yaqub Beg’s army were either arrested or executed. The total death toll from this rebellion may exceed 12 million.[5]

5 Yellow Turban Rebellion

Although 19th-century China was a place of unremitting horror, ancient China was no better. In fact, the AD 200s were the apex of Chinese brutality until the coming of Mao. Between AD 184 and 205, Chinese peasants rose in rebellion against the Han dynasty. Known as the Yellow Turban Rebellion, this devastating war may be the only war in history inspired by the teachings of Taoism. Zhang Jiao, the rebellion’s first leader, tapped into the economic malaise of the Later Han dynasty to make himself a fearsome warlord. The peasants’ complaints were many: high taxes, high debts owed to landowners, and the growth of a tenant farmer system that included mandatory peasant labor (corvee) for noble families and mandatory military service. Making the situation worse was the weak leadership of the Han dynasty. Since the death of Emperor He, it had fallen into the hands of court manipulators, empresses and their families, and eunuchs. Corruption became the norm, with the buying and selling of government positions. The peasants suffered the most, especially during droughts and floods. When these appeared, the incompetent men in charge of the state granaries often had to admit that there was no food. Driven by starvation and anger, the peasants formed militias. Zhang, a master of the Taoist religion, was named as the rebellion’s first leader because he was a beloved healer among the peasants of Hebei Province. Zhang’s slogan was “the Blue-Gray Heaven (representing the Han) is dead, the Yellow Heaven (the color of Taoists) will be established.”[6] The peasant army, which was known for wearing distinctive yellow scarves, proved to be effective fighters. Early in the rebellion, the province of Shandong, the home of Confucius, Mencius, and Zisi, was captured by the rebels. From there, Zhang and his brothers attempted to spread the message of Taoism, which included equal rights for peasants and land reform. These messages, along with the supposed healing powers of the Zhang family, saw rebel victories above the Yellow River and in and around Beijing. To put down the rebellion, the Eastern Han organized a large army and began offensives in the areas where rebellion activity flourished. In AD 184, Zhang Jiao was killed during the defense of Guangzhou. The leadership of the rebellion then fell into the hands of the other two Zhang brothers, while smaller bands of Yellow Turbans turned to banditry to keep the war alive. Although the Han managed to win the war, the cost of quashing the rebellion weakened the dynasty to the point that General Cao Cao, a warlord and bureaucrat of the Eastern Han who first tasted battle against the Yellow Turbans, leveraged Han weakness to establish a separate state known as Cao Wei. It is believed that the Yellow Turban Rebellion resulted in between three million and seven million deaths.

4 War Of The Three Kingdoms

The Yellow Rebellion led directly to the collapse of the Han dynasty. Since power vacuums invariably lead to bloodshed, it was only a matter of time before a civil war broke out in China. That is exactly what happened in 220. Three rival kingdoms—Wei, Shu, and Wu—went to war with each other to unify China. The war ended in 266 when the Jin dynasty of Northern China conquered the Eastern Wu. When the Eastern Han state collapsed, Cao Pi, the son of Cao Cao, took control of the Wei state in Northern China. The Wei Kingdom included several former Han generals. Other Han generals used the chaos to set up their own kingdoms. General Shu-Han created the Shu Kingdom in what is today Sichuan Province, while another former Han general established the Wu Kingdom at Nanjing. These kingdoms almost immediately fell into fighting one another. In either 263 or 264, the Wei defeated and conquered the Shu. Two years later, Sima Yan/Wudi, one of the Wei generals, took the Wei throne and established the Jin dynasty. In 280, the Jin defeated the Wu and briefly united all the lands of the former Han dynasty. China would continue to be controlled by the Jin until 420. The Three Kingdoms period is best known in China as the inspiration for The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, a classic of Chinese literature and one of the world’s first novels. Written by the Shaanxi native Luo Guanzhong, the novel was published in the 14th century. The beauty of Luo’s words and several infrastructure improvements (including new irrigation and shipbuilding programs fueled by the Silk Road) have served to obscure the awful realities of this time period.[7] The true horror of the war is captured by this statistic: During the Han dynasty, China’s population stood at 54 million. When the Jin took power, China’s population was 16 million. This means that 36–40 million people died during the 60-year conflict.

3 Taiping Rebellion

Religious fervor gripped the late Qing Empire. Specifically, between 1850 and 1864, a rebel general named Hong Xiuquan proclaimed himself the brother of Jesus Christ and the prophet of a new era for the Chinese people. Within the usual strictures of Chinese history, Hong should never have amounted to much, let alone led a rebellion that commanded a major city and almost brought down an empire. Hong was born in 1814 in the southern province of Guangdong (Canton). As a young man, he took the civil service exam that was required of all aspiring bureaucrats. He failed this test multiple times. Defeated, Hong decided to head home. On the journey in 1847, Hong had several fevered visions for 30 days, including one where he and his brother fought the demons of the Kingdom of Hell. To stop demons from destroying the world, Hong declared himself the “Heavenly King, Lord of the Kingly Way.”[8] His vision drew recruits from the poor and destitute classes of southern China. Hong’s Taiping Tianguo (Heavenly Kingdom of Great Harmony) promised Heaven on Earth, the removal of hated Qing, and the removal of foreign powers (specifically the British and French) from China. The Taiping vision of a new China included one where Christianity was wedded with Confucianism, land reform and common property shared among peasants was the norm, women were given an equal status with men in society, and abstinence from alcohol and opium would be encouraged. By the late 1850s, the Taiping controlled the important port city of Nanjing (renamed Tianjing) and a third of China. At the height of Taiping power, its army stood at a million men and women. Beginning in 1853, the Taiping army began making expeditions northward in the hopes of capturing Beijing, the Qing capital. Although the Taiping scored several victories near the Yellow River, they never managed to capture Beijing. The movement soon became fratricidal when Yang Xiuqing, the Minister of State, tried to replace Hong. Hong had Yang and his followers executed. Then, when General Wei Changhui began to grow “haughty,” Hong had him murdered as well. These killings inspired several Taiping generals to switch sides and convinced Western powers to form their own armies to stop the Taiping. The best-known anti-Taiping force was the Ever Victorious Army (EVA). This army was raised in Shanghai by British, American, and French merchants. The army’s Chinese foot soldiers were commanded by an odd assortment of military adventurers, mercenaries, and professional soldiers. Frederick Townsend Ward, a 29-year-old experienced sailor from Salem, Massachusetts, and Charles “Chinese” Gordon, a British Army officer who would later die in the Sudan, led the EVA with pluck and plenty of Western weapons. The EVA and the regular Qing Army, itself well-supplied with British and French weapons and ships, ended the rebellion in 1864. The devastation of the Taiping Rebellion was so great that certain Chinese provinces did not recover from the damage until well into the 20th century. It is believed that 20–30 million Chinese soldiers and civilians died during the war.

2 An Lushan Rebellion

The worst military rebellion in Chinese history was led by a man who once pledged his loyalty to the emperor. Between 755 and 763, An Lushan, a former general of the army of the Tang dynasty, brought down the Tang dynasty, captured two of the most important cities in Chinese history, and nearly eradicated entire populations as a result. An Lushan did not begin as a rebel. In fact, he was a hero for much of his life. An Lushan (aka Xiongwu) was neither Han Chinese nor a member of an East Asian ethnic group. His father’s family came from Bukhara in today’s Uzbekistan. An’s father was a Sogdian, an Indo-European people noted for their red hair and artistic creativity. It was the Sogdians who dominated the Silk Road trade long before the Chinese emperors. An’s mother was an Eastern Turk (Gokturk) whose noble family had been involved in the Turkic takeover in Mongolia in the fifth century AD. An Lushan’s ethnicity did not hurt him. Emperor Xuanzong of the Tang dynasty encouraged non-Chinese groups to join the Tang bureaucracy, specifically the army. Like the Late Roman Empire, the Tang dynasty valued these foederati for their battle prowess and excellent horsemanship. These soldiers were also desperately needed by the Tang, who found themselves in the eighth century unable to protect their borders from outside invasions. At the Battle of Talas in modern-day Kyrgyzstan, the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad defeated a Tang army supported by Sogdian and Turkic mercenaries. After this battle, Central Asia fell into the Muslim, rather than Chinese, sphere of influence. The only bright spot for the Tang dynasty was their minor victories in Tibet. On December 16, 755, General An Lushan, who had been appointed the commander of a 150,000-strong army by Emperor Xuanzong, marched against the Tang court. An justified this rebellion because he claimed that he had suffered insults at the Tang court from Yang Guozhong, his political rival. In no time, An’s force captured the city of Luoyang in Henan Province. At the time, Luoyang was the eastern capital of the Tang Empire. At Luoyang, An declared the creation of the Great Yan dynasty with himself as the first emperor. General An’s forces then moved to capture southern China as well as the Tang capital of Chang’an (Xi’an). An made sure to treat captured Tang troops well so that they would defect en masse.[9] It took the Great Yan army two years to capture Henan Province. In the meantime, the Tang hired 4,000 Arab mercenaries to defend Chang’an. The Yan looked unable to take the city. However, Yang Guozhong decided to fight the Great Yan on the flat plains outside of Chang’an. An’s men easily defeated this Tang force, and thus, Yang Guozhong and Emperor Xuanzong had to flee to Sichuan. Xuanzong eventually abdicated, and Chang’an became the Great Yan’s capital. An Lushan’s rebellion faced its first setback in 757. In that year, a Tang army made up of 22,000 Arab and Uighur recruits retook Chang’an. These Muslim troops would intermarry with local Han women, thus creating today’s Hui Muslim minority. In that same year, An Lushan’s son, An Qingxu, killed his father and then was killed by An Lushan’s friend, Shi Siming. Siming would also be murdered by his son, and the instability of the Great Yan court led to the defection of hundreds of generals back to the Tang court. By 763, internal strife and renewed Tang offensives ended the rebellion. The final death toll was staggering. In 754, the recorded Chinese population stood at over 52 million. By 764, only 16.9 million Chinese were left alive. That means that 36 million people perished as a result of An Lushan’s quest for power.

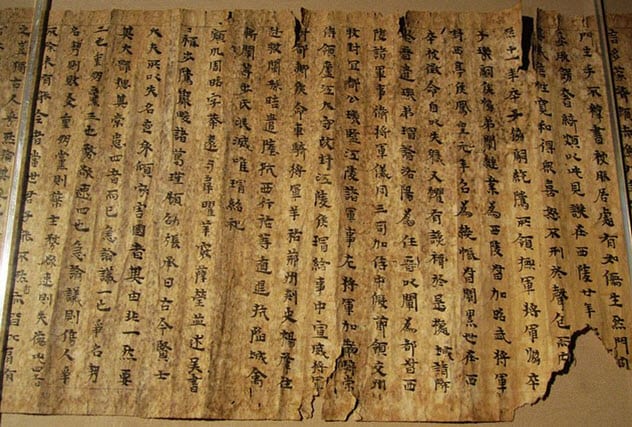

1 The Manchu Conquest Of The Ming Dynasty

The last Han Chinese dynasty of China was the Ming dynasty, which lasted from 1368 until 1644. The Ming are celebrated today not only because of their beautiful artwork, especially their use of porcelain, but also because they overthrew the yoke of the Mongol Yuan dynasty while also establishing protectorates in Vietnam and Myanmar. The successor to the Ming, the Qing dynasty, would last for 276 years and would increase the imperial holdings of China to its largest extent. The Qing Empire conquered Tibet, Mongolia, and parts of Siberia. Today, many Chinese celebrate the Qing for their expansion of Chinese territory. However, if these praises come from the Han Chinese, then they are tragically ironic. After all, under the Manchu Qing, Han Chinese people were officially second-class citizens and suffered one of history’s worst conquests. The Manchu people of Northern China, who are ethnically related to other Tungusic peoples like the Evenks of Siberia, the Orochs of Russia and Ukraine, and the Sibe of Xinjiang, were led in the 17th century by the Jurchen warlord Nurhaci. For 30 years, Ming China enjoyed relative peace because Nurhaci was too busy militarily uniting the five Jurchen tribes of Northern China. Once this was accomplished, Nurhaci established the Eight Banners, a patrilineal system for military and civilian governance. In 1616, Nurhaci declared himself the khan of the reconstituted Jin dynasty (aka the Later Jin). To show his wealth and status, he created a dazzling palace at his capital in Mukden (today’s Shenyang). Two years later, Nurhaci declared war on the Ming after commissioning a document entitled “Seven Great Vexations.”[10] In it, Nurhaci blamed the Ming government for favoring the Yehe tribe, one of the northern tribes that Nurhaci had gone to war against. Until his death in 1626, Nurhaci went from victory to victory, defeating Ming armies, Mongol tribes, and Korea’s Joseon dynasty. Despite the formidable Jurchen/Manchu military, the Ming dynasty collapsed from within. Owing to financial instability and endless peasant rebellions, Han Chinese officials asked Nurhaci’s successor, Hong Taiji, to name himself emperor. On April 24, 1644, Beijing was captured by a peasant army led by Li Zicheng, who in turn declared the formation of the Shun dynasty. A little over a month later, at the Battle of Shanhai Pass, Wu Sangui of the Ming Army allied himself with the Manchus and opened the Great Wall of China at the Shanhai Pass to let Prince Dorgon’s Manchu army enter the Central Plains. From this point until 1662, the Qing dynasty of the Manchus slowly defeated the Shun and Xi dynasty of the peasant leader Zhang Xianzhong. This war of conquest more than likely killed over 25 million people. The conquest exposed the Qing aptitude for cruelty, too. Qing judges instituted a punishment known as “death by a thousand cuts” (lingchi). Criminals sentenced to this punishment suffered innocuous cuts for hours before being strangled and decapitated. Although this punishment was rare, far more common was the queue haircut. This haircut, which featured a completely shaven head except for a long pigtail, became a part of Han Chinese life when Qing Emperor Shunzi ordered all Han men to adopt it as a sign of submission. When Han Chinese men revolted against this order, the Qing instituted a policy of decapitation. Namely, if any man refused to wear the hairstyle, then he’d lose his head. The fear of the Qing and the Manchus was so great that, even as late as the 1920s, long after the overthrow of the last Qing emperor in 1911, many Han Chinese men still refused to cut their queues. Benjamin Welton is a freelance writer based in Boston. Read More: Twitter Facebook The Trebuchet