10St. Augustine Donkey

Not all mysterious graves contain human remains. In St. Augustine, Florida, a local archaeologist was baffled by a unique and bizarre burial of a donkey. The animal was discovered under 120 centimeters (4 ft) of earth and dates to the second half of the 17th century. The animal has an indent on the top of its skull and was likely killed by a blow to the head. But what happened afterward is hard to explain. All four of the animal’s limbs have been carefully disarticulated. No butchering marks appear on the bones. In fact, they’ve been removed so carefully that the animal almost certainly wasn’t used for food. After removal, the limbs were placed on top of the donkey and arranged to face north–south. Digging a bigger hole would’ve been quicker than removing the limbs with such precision, so convenience isn’t a likely explanation. Carl Halbirt, who found the animal, said, “I don’t think we’ll ever know the complete story.” He’s looked for similar burials but couldn’t find any on record. Donkeys were used in the area at that time as pack animals to carry coquina from a nearby quarry for use in building. While that explains why the beast was in the area, it offers no clues as to why someone would’ve gone to so much seemingly needless effort to dispose of the body.

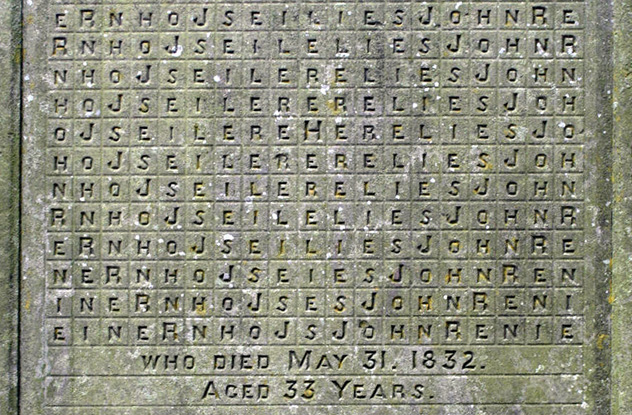

9John Renie

Welsh house painter John Renie died in 1832. The unusual inscription on his grave takes the form of a grid, 19 squares across and 15 squares high. In each square is a letter. The center row, for example, reads “o J s e i L e r e H e r e L i e s J o.” You can make out some clear words. “Here” and “Lies” are in that in that string above, and you can see the start of “John.” But why the jumble? After 170 years, a local TV station finally analyzed it, determining that it was a type of acrostic puzzle. Starting at the H in the very center and working outward, the sentence “Here Lies John Renie” can be read in 46,000 different ways. Some people say Renie was trying to fool the devil, to keep his soul safe. The local vicar thinks they’re taking the inscription too seriously. He expects it “was just a bit of fun” meant to provide entertainment for those that saw it.

8Duffy’s Cut

In June 1832, a ship carrying dozens of young Irishmen docked in Philadelphia. The men had crossed the Atlantic to work as railway laborers for a contractor named Duffy but had the unfortunate luck to arrive as a cholera outbreak was tearing through the region. It hit the men’s shanty, and official records show that eight were killed and buried nearby. Rail official Martin Clement put a granite enclosure around the area in 1909 as a monument. Clement became president of Pennsylvania Railroad and kept a file on the deaths on the stretch, which was known as Duffy’s Cut. His executive assistant got the file in the 1960s, and in the early 2000s, the assistant’s twin grandsons, Bill and Frank Watson, took a look at it. The file reported the death toll as being 57 people, way higher than the official number. The Watsons began digging—literally. In November 2005, they found a clay pipe adorned with shamrocks. After hiring a geoscientist in 2009, they started unearthing bodies. Over the next couple of years, they found six more bodies, and a pattern began to emerge. Three skulls showed signs of blunt trauma. Another had a bullet hole. University of Pennsylvania Museum anthropologist Janet Monge, part of the team, concluded, “I actually think it was a massacre.” Researchers speculate that the shanty was quarantined, and many of the workers were killed when they tried to escape.

7Nick Beef

The Shannon Rose Hill Memorial Park Cemetery in Fort Worth, Texas has a small granite stone with the name “Oswald” on it. The man buried there is Lee Harvey Oswald, John F. Kennedy’s assassin (unless, of course, JFK was killed by his own Secret Service). Since 1997, a nearly identical gravestone has sat beside it bearing the name “Nick Beef.” Who is Nick Beef? Some suggested that it’s a comedian named Nick Beef, who placed the stone there as part of a standup act. Many people interested in the Kennedy assassination simply remained baffled. One theory was that the stone helped people find the grave, since the cemetery doesn’t give out directions to the Oswald plot. They now refuse to give directions to Nick Beef, as well. In reality, Nick Beef is Texas native Patric Abedin, who now lives in New York City. He bought the plot in the 1970s simply because it was available. He created the name as a joke in a diner, and he later adopted it as a pseudonym while working as a freelance writer. When Abedin’s mother died in 1996, he returned to Texas and paid a visit to his plot of land in the cemetery. He decided, once again on a whim, to install a gravestone there. His use of “Nick Beef” as a pseudonym meant he had a credit card under that name, so the cemetery allowed him to put the marker there. He is very much alive, and the plot is empty. He says it’s not a joke. It’s just a personal thing. Oswald’s body won’t be getting a neighbor anytime soon. When Abedin dies, he’d like to be cremated.

6James Leeson

James Leeson died in 1794 at the age of 38. Not much is known about his life, but his gravestone is probably more famous for its own sake than any other in New York. Among the tombstone’s decorations are an hourglass with wings, to represent how quickly time passes. A flaming urn symbolizes the soul’s immortality, and stonecutters’ tools reflect that Lesson was a Mason. This Masonic connection left the grave’s most interesting feature—a coded message curving across the top of the tombstone. It’s written in a Masonic cipher based around the tic-tac-toe game board. When it first appeared, no one could figure it out. A century later, in 1889, the key was published. The message says “REMEMBER DEATH.” Combined with the hourglass, Leeson was saying that we each only have a limited time, and we shouldn’t waste it. James Leeson puzzled New Yorkers for a century, and continues to draw visitors today, with an obscure 18th-century version of YOLO.

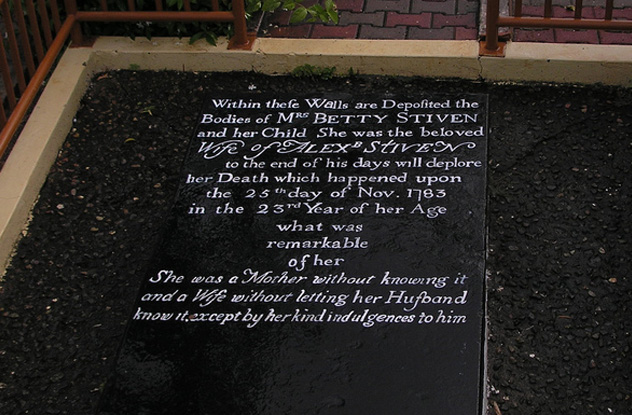

5Betty Stiven

In the town of Plymouth on the Caribbean island of Tobago is a tombstone belonging to a woman named Betty Stiven. The inscription reads: “Within these walls are deposited the bodies of Mrs. Betty Stiven and her child. She was the beloved wife of Alex B Stiven to the end of his days will deplore her Death, which happened upon the 25th day of Nov. 1783 in the 23rd year of her age. What was remarkable of her, she was a mother without knowing it, and a wife without letting her husband know it except by her kind indulgences to him.” For centuries, the meaning of those words has been a mystery. While it’s very possible to become a father without realizing it, mothers go through a process that’s rather difficult to miss. Being someone’s wife without their knowing about it also has its challenges. As the sign next to it says, the inscription “baffles interpretation.” One theory is that Betty was a slave and Alex Stiven was her owner. He impregnated her when she was 12, and then she got ill and was confined to her bed. During one of her bouts of unconsciousness, she gave birth to four children, one stillborn. Alex Stiven gave them to other slave women to raise, ordering them not to tell Betty. The wife situation is explained by how sex constituted a union at that time, without the requirement of a marriage ceremony. We could consider another possibility. The engravers might not have meant the statements literally. If an older female figure made a difference in your life, you could say she was like a mother without her realizing how much she meant to you. The wife part is a little harder to figure out, admittedly. Either way, people continue to speculate, and Betty Stiven’s tombstone has become a popular tourist attraction, whoever she was.

4Anaheim Cemetery’s Tricky Body Count

Anaheim Cemetery was the first cemetery in Orange County, California open to non-Catholics. As a result, it became the burial destination of choice for the huge numbers of Chinese migrants who came to work in California in the late 19th century. A patch of the cemetery is marked off with Chinese dawn redwood trees, planted in 1989. Yet the cemetery owners have no idea whether any bodies lie under that section of ground. Records note 33 burials around the turn of the century, but the grave markers are long gone. They were made of wood, and caretakers burned them to get rid of weeds. Chinese workers weren’t thought of very highly a century ago. The immigrants preferred their burials in the US to be temporary. As soon as they could afford it, bodies would be dug up and shipped back to China to be buried in their homeland. While the burial records survive, all interment records have been lost. The body count will probably stay unknown, as the attitude toward the workers has improved. According to a trustee who looks after the cemetery, “Even if we found this area to be empty, I can’t see us using it. The Chinese played an important part in the development of Anaheim, and we can’t forget that.”

3Oxford Viking Grave

When Oxford archaeologists discovered a mass grave of 34 bodies dating to the end of the 900s, they thought they’d stumbled upon an execution cemetery. Such cemeteries are a common feature of the British archaeological landscape. Twenty have been found so far. During the rule of Edgar the Peaceful in the 10th century, as many as 3 percent of the country’s men were executed and dumped in such graveyards. As they investigated further, the details they found didn’t fit the theory. The men in the grave had been killed violently and dumped all at the same time, rather than over decades as expected. They’d also met their end in a variety of ways. A dozen had been stabbed in the back, 27 had broken skulls, and 20 showed injuries to their spines and pelvic bones. Many had also suffered some serious burns to the top halves of their bodies. There was a common profile, too. The men were aged between 16 and 35 and were more well built than the average citizen. Tests on the chemical composition of the bones showed they ate more fish and shellfish than the locals. The team had likely found a mass grave of massacred Viking warriors. A year later, another team found a grave of the same profile 145 kilometers (90 mi) southwest. This one contained 54 well-built young men, all decapitated. Analysis of oxygen isotopes in tooth enamel showed that the men had come from much farther north, with at least one a native of the Arctic circle. The men were likely victims of the St. Brice’s Day Massacre by King Aethelred the Unready. On November 13, 1002, he decreed that “all the Danes who had sprung up in this island, sprouting like cockle weeds amongst the wheat, were to be destroyed by a most just extermination.” The nature of the graves actually paints the events in a slightly more sympathetic light, as only fighting men based near the king’s seat of power seem to have been targeted.

2The Massacre In A Well

In 2013, archaeologists spent five months excavating a site at the town of Entrains-sur-Nohain in Burgundy. For four centuries at the start of the first millennium, the area was home to the Roman city of Intaranum. The dig revealed roads, stone houses, and wells for supplying wealthy residents’ private baths. The bottom of one such 130-centimeter-wide (4.3 ft) well revealed a gruesome surprise. More than 4 meters (13 ft) down, the diggers found bones from over 20 bodies. The remains came from men, women, and children—it was a collection of civilian casualties. They weren’t part of the Roman settlement, as they were carbon dated to be from sometime between the 8th and 10th centuries. Three competing theories explain how so many corpses ended up being thrown into an old hole. One says an epidemic swept through a village. Another suggests that they were unwitting victims of a nearby battle. On June 25, 841, a battle took place 25 kilometers (15 mi) north of the site. Tens of thousands of troops fought for secession for the Carolingian Empire. Marching armies aren’t known for leaving civilians in peace, and a band of combatants may have raided the village before or after the battle. A third possibility is equally violent, as gangs of Vikings marauded all over France in the second half of the ninth century. Even if history’s most infamous pillagers weren’t behind the deed, they could well have stirred enough unrest to create bands of brigands among the locals.

1Unusual Saxon Burials

When archaeologists in the English town of Ramsgate uncovered a pair of skeletons in 2008, they thought they’d found a married couple. The two figures had been buried side by side. One lies on its back; the other is on its side with its arm over its partner. It’s an unusual burial, and the skeletons date from sometime before the Norman conquest in 1066. Yet both skeletons are over 180 centimeters (6′), unusually tall for the period. Originally, the left skeleton—the one performing the cuddling—was believed to be female. Yet further examination suggested that both skeletons were men. It’s possible that they were warrior companions, but there are no artifacts to offer clues. A different Saxon mystery from the seventh century was uncovered in Cambridge in 2012. The skeleton of a teenage girl combines two extremely rare status symbols. She was buried with a gold- and garnet-encrusted cross stitched to her clothing, the fifth such pectoral cross in the UK. She was also buried on a wooden bed, only the 15th person discovered that way in the UK. There’s only one other possible burial combining a cross with a bed, and it’s from all the way in the 19th century. The girl was almost certainly of high status, possibly even royalty. She could have been a figurehead in the early Christian church, which was just beginning to make an impact in Britain. In addition to the cross, she was also buried with pagan items, including glass beads and an iron knife, which didn’t fall out of Christian favor until the next century.