10Rene DescartesPassion For Cross-Eyed Ladies

The Father of Modern Philosophy, Rene Descartes (1596–1650), maintained close friendships and correspondence with powerful and wealthy women, such as Queen Christina of Sweden and the exiled Princess Elizabeth of England. The women in his personal life were a different story. Descartes never married and only had one child, an illegitimate daughter, with one of the servants in his home. And, until early adulthood, Descartes’s greatest passion was reserved for women with crossed eyes. In a letter to Queen Christina, Descartes explains that, once he finally reflected on his unique attraction toward cross-eyed women, he realized that it stemmed from a youthful crush he had on a girl with crossed eyes. Descartes stated, “I loved a girl of my own age . . . who was slightly cross-eyed; by which means, the impression made in my brain when I looked at her wandering eyes was joined so much to that which also occurred when the passion of love moved me, that for a long time afterward, in seeing cross-eyed women, I felt more inclined to love them than others, simply because they had that defect; and I did not know that was the reason.” Descartes concluded that this initial crush had left an imprint on his brain and, therefore, it was not a reasoned attraction. Rather, it was his subconscious mind causing the feelings. True to philosophical form, Descartes used his free will to rid himself of the irrational attraction.

9Albert CamusFear Of Early Demise

The noted philanderer and philosopher, Albert Camus (1913–1960), grew up in an impoverished household with no running water or electricity. As head-of-household, Camus’s stern grandmother used a bullwhip to keep her family in line. Even with this difficult start to life, Camus managed to earn a scholarship that enabled him to attend high school. At the age of 17, however, he narrowly survived a bout with tuberculosis and was forced to take a year off from school to recover. Yet again, Camus persevered, returned to school, and became a published author even before entering the University of Algiers. In spite of his ability to survive and his early successes in life, Camus was obsessed with the notion that he would die at an early age. He once told a girlfriend that he “sensed evil floating in the air.” For Camus, this fear created an obsession with death in general. Not only did he carry a suicide note written by a friend of Leon Trotsky’s in his pocket, but he asked an American girlfriend to send him copies of Embalmer’s Monthly magazine. Filled with pessimism and fueled by fear, Camus was determined to complete his writings before he died. Even winning the Nobel Prize was something of a bad omen to Camus, who believed that the award was a stamp on the end of a person’s career. The pressure he felt to complete his magnum opus intensified and continued to haunt him until his death, when his fears came to fruition. On January 4, 1960, Camus died in a car crash at the relatively young age of 46.

8Immanuel KantRigid Schedule

Obsession was a way of life for Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). While Kant is often noted for his hypochondria, he had an even more intense and prolonged obsession with his daily routine. In 1783, just after purchasing a home, Kant decided that it was necessary to structure his daily schedule. Thus began the rigid routine Kant would follow until his death in 1804. Timed precisely, Kant would awaken just before 5:00 AM, drink a cup of tea, and smoke exactly one pipe. He would then work on his lectures and writings until his lectures began at 7:00 AM. After his lectures ended at 11:00 AM, Kant worked on his writings again until his 1:00 PM lunchtime. After lunch, rain or shine, Kant took his legendary one-hour walk in the heart of Konigsberg. The walk was so consistent that it is said his neighbors could set their clocks by it. The path Kant walked was later named the Philosophengang, or “The Philosopher’s Walk.” After his walk, Kant would sometimes socialize with a friend or two, and then he would head home to work and read until 10:00 PM, at which time he went to bed.

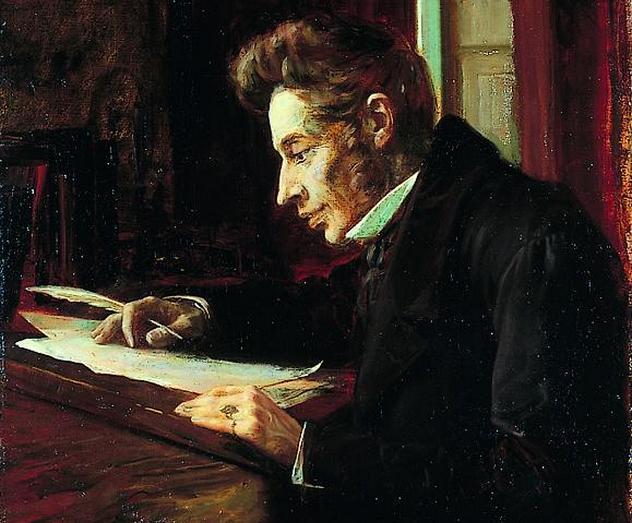

7Soren KierkegaardFamily Curse

Before Kierkegaard (1813–1855) had reached the age of 25, five of his siblings and both of his parents had died. Just a few years before, his father had confessed to his son that he was destined to watch all of his children, including Kierkegaard, die before him because he had brought God’s wrath down upon them when he had cursed God as a young boy. Kierkegaard fully accepted his father’s conclusion about their family’s bad luck and he accepted the idea that he was facing an early death. Although his father died in 1838, with Kierkegaard still alive and well, Kierkegaard still believed that he was cursed and that God would take his life at an early age. This knowledge sparked Kierkegaard to write prolifically in an attempt to say everything before his early passing. He preceded one of his early works, written shortly after his father’s death, with a telling quotation from King Lear, Act 5, Scene 4, a part of which reads: “A guilt must weigh on the entire family, God’s punishment must be upon it; it was meant to disappear, expunged by God’s mighty hand, deleted like an unsuccessful attempt.” Like Camus, Kierkegaard’s fears came to fruition when he died in 1855. He was just 42 years old.

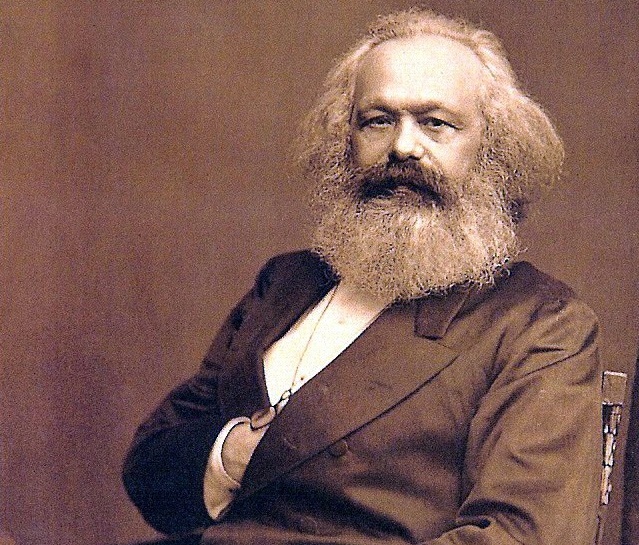

6Karl MarxFrantic Idea Generation

Karl Marx (1818–1883) was the co-author of the seminal work The Communist Manifesto. Although he is considered one of the most influential theorists of the 20th century, Karl Marx’s personal life was filled with chaos and disorder. Partially because of his dire financial situation—which largely resulted from his and his family’s expulsion from France because of his political writings—and partially because of his personality, Marx would work intensely, but only in bursts of productivity that were often followed by bouts of exhaustion, illness, and a cessation of work and missed deadlines. Contributing to the chaos, Marx often started a work just to put it down half-finished when he wanted to begin another. Marx’s inner chaos, however, is best exemplified by the compulsive manner with which he generated ideas for his philosophical works. While working, Marx would put an idea to paper and then he would stand up and begin frantically walking around his work table. When an idea eventually struck him, he would quickly sit down, write out the idea, and then begin the process over again. It’s little wonder that Marx would often collapse from exhaustion after a long work day.

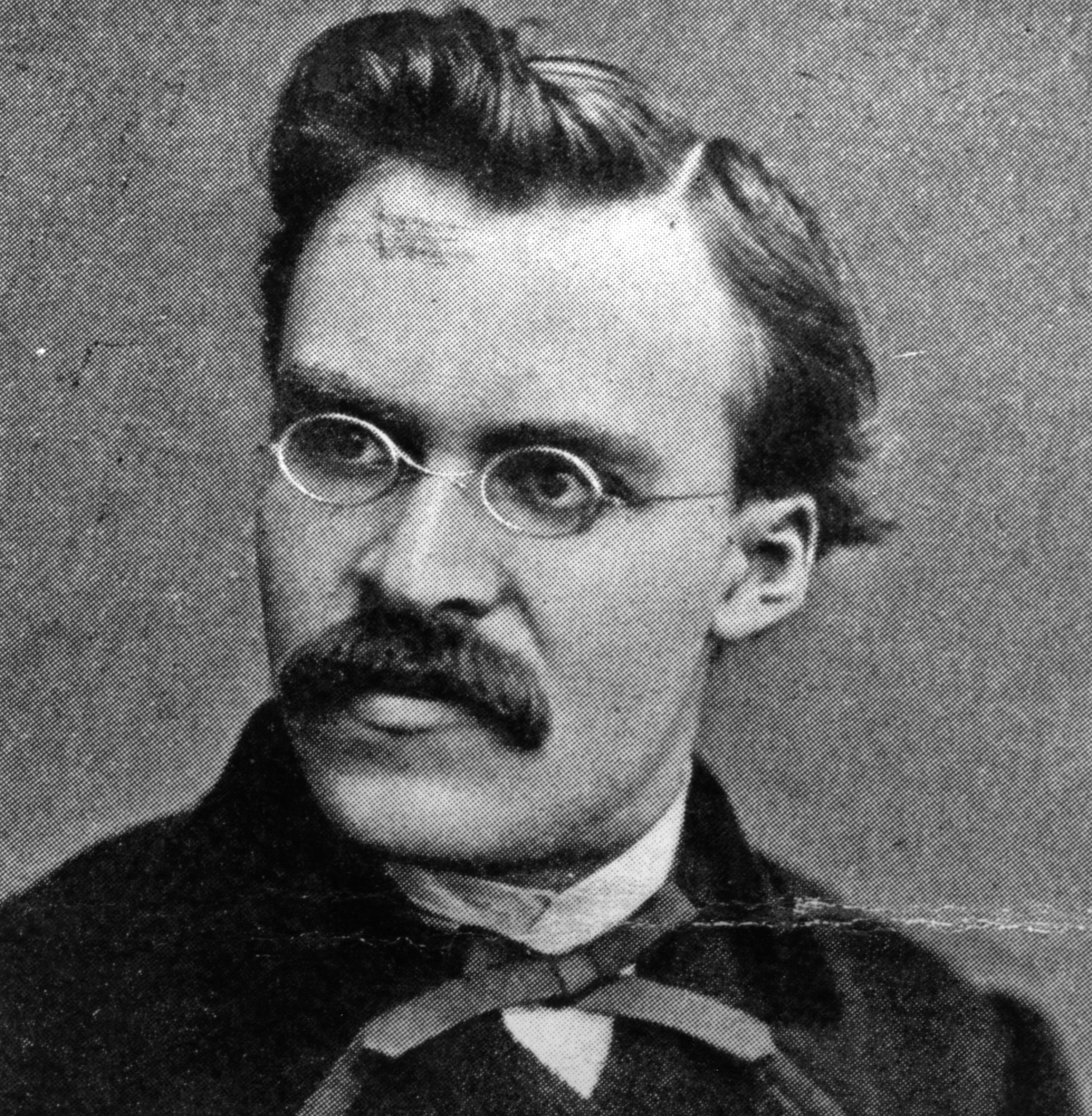

5Friedrich NietzscheFruit

At the tender age of 24, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) was appointed as Chair of Classical Philology at the University of Basel. He wrote prolifically and became a well-respected philosopher during his lifetime. For all of his successes, however, Nietzsche’s life was plagued by a hefty list of medical problems. In order to alleviate his suffering from chronic headaches, persistent vomiting, and a painful digestive disorder, Nietzsche tried a long list of medications as well as a variety of diets. Ironically, it is very likely that Nietzsche’s obsession with fruit was responsible for inflaming his digestive discomfort. According to the innkeeper at the Alpine Rose, where Nietzsche stayed for an extended time in 1884, Nietzsche’s daily food intake consistently included a beefsteak for breakfast and fruit for the rest of the day. Not only did Nietzsche purchase fruit from the inn and from local Italian vendors, but he received baskets of fruit shipped to him by his friends as well. This wasn’t a small amount of fruit. Rather, on more than one occasion, Nietzsche ate almost three kilograms (6.5 lbs) of fruit during the course of a single day.

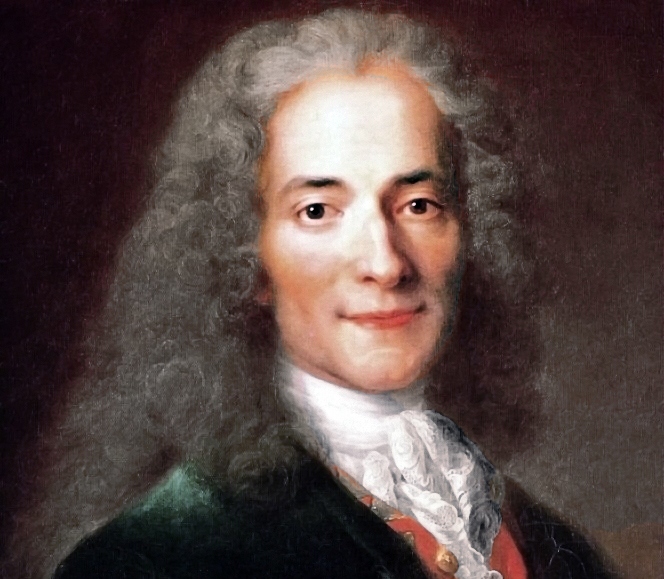

4VoltaireConstant Need For Coffee

As one of the most famous Enlightenment philosophers, Voltaire (1694–1778) is extolled for his wit and satire. It is possible, however, that he would not have been quite as witty or satirical without the enormous amount of coffee he ingested daily. Whether he was at home or relaxing with friends at the Cafe de Procope in Paris, Voltaire drank 20 to 40 cups of coffee every day. He enjoyed coffee so much that he willingly ignored the advice of his physician, Theodore Tronchin, to stop drinking it. He even regularly paid exorbitant fees to have luxury coffee imported for his personal use. It should be noted that a quote often attributed to Voltaire is misattributed. Numerous sources claim that, in response to the assertion that coffee is a slow poison, Voltaire stated, “It may be poison, but I have been drinking it for sixty-five years, and I am not dead yet.” Sometimes the quotation is presented with “sixty-five years,” “eighty-five years,” or “fifty years.” While the quotation is certainly memorable (and useful for coffee lovers), there is no source for this quotation belonging to Voltaire. William Harrison Ukers makes a strong case in his All About Coffee that the quotation belongs to Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle. First, in Meidinger’s German Grammar, published in 1800, Fontenelle is given the credit for the quotation. Secondly, the correct quotation is: “I think it must be [a slow poison], for I’ve been drinking it for eighty-five years and am not dead yet.” Given that Voltaire died at the age of 84, while Fontenelle lived to be nearly 100, the evidence seems to support Fontenelle as the origin for the quotation.

3Georg Wilhelm Friedrich HegelHis Favorite Clothes

Except for the death of his mother when he was 13, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831), who would become one of the most renowned proponents of German Idealism, had an uneventful and literature-filled childhood. His early adult years were comprised of seminary school, writing, and tutoring for an aristocratic family in Bern. Before the age of 45, Hegel had a successful marriage, a family, and a good job as the editor of a well-respected literary journal, the Heidelberger Jahrbucher. But even the most seemingly normal philosophers had interesting quirks. For Hegel, it was his nightgown and black beret. While working at home, Hegel would consistently wear his nightgown over his day clothes and don an oversized black beret on his head. In one incident, when Hegel’s friend Eduard Gans dropped by for a visit, he found Hegel in his study, shuffling through a mountain of unorganized papers, wearing his nightgown over his day clothes along with the beret. This odd-looking outfit gained Hegel some notoriety when a lithographer, Julius L. Sebbers, portrayed Hegel in his study, wearing the nightgown and black beret. Hegel very much disliked the picture, which caused his wife to remark that he didn’t like the picture because it resembled him a bit too much.

2Jean-Paul SartreFear Of Sea Creatures

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) was a prolific writer and political activist who, during the course of his life, defended such notable figures as Karl Marx, Fidel Castro, and Che Guevara. Like Camus, Sartre won the Nobel Prize and he was none too pleased about the award; but Sartre flatly refused to accept the prize along with the award money. For Sartre, it was a deeply philosophical act: Human-made institutions like the Nobel Prize only worsened the conditions of men, all of whom were “condemned to be free.” For all of his intellectual confidence, however, Sartre had one enduring weakness: crustaceans. As a child, Sartre was scarred by a painting of a claw coming up out of the ocean, attempting to grab a person. Thereafter, Sartre had an obsessive fear of crustaceans and other sea creatures. His fear was so intense that he once had a panic attack after getting into the water of the Riviera with his long-time love, Simone de Beauvoir. He believed that a giant octopus would rise up from the dark depth of the water and drag him to his death. On another occasion, after consuming a mind-altering drug, Sartre had visions of lobsters following him everywhere he went. This obsession with sea creatures can also be seen in the imagery he uses in many of his literary works, such as The Condemned of Altona, “Erostratus,” and Nausea.

1Arthur SchopenhauerHis Poodles

Even though Arthur Schopenhauer’s (1788–1860) family was financially well-off, homelessness became the theme for his life. An intellectual vagabond, Schopenhauer took the perspective that he belonged to no place and to no person. Even his birthplace, Danzig, Germany, meant nothing to Schopenhauer, since he and his family had to quickly abandon their home when Prussia annexed the city. Schopenhauer was only five years old at the time. No city thereafter managed to capture Schopenhauer’s loyalties. Similarly, after the loss of his father just as Schopenhauer entered adulthood, Schopenhauer could find little affection for other people, including his own mother. Expressions of this disconnection from humanity can be seen in his pessimistic philosophy. Schopenhauer’s pessimism and personality led him to fill his human need for companionship with pet poodles. Starting in his schooldays and not ending until his death, Schopenhauer kept a flow of poodles, all of which had the same name, Atma, and the same nickname, Butz. The oddity of calling all of his poodles by the same name was intended as a compliment, because the word “Atma” is a Hindu concept developed in the Bhagavad Gita from Sanskrit meaning “inner self,” or the transcendent soul. To Schopenhauer, each of his pets, rather than being an individual animal with its own personality, expressed the highest and most fundamental reality of “poodle.” I love to read; I love to write. If it is intellectual, I am intrigued.