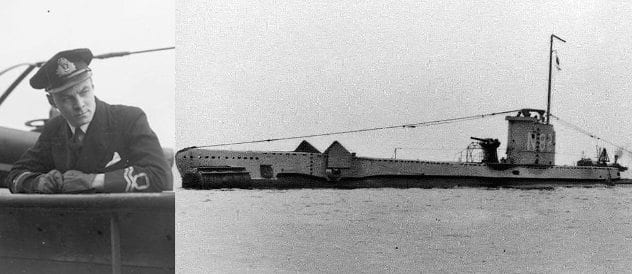

10 Edward Young

On July 19, 1941, the HMS Umpire, a brand-new British U-class submarine, departed Sheerness for sea trials. The Umpire was sailing along the surface when she collided with a trawler, which could not see the submarine in the early morning darkness. The submarine’s commander and three others were outside on the bridge during the collision and were left to tread water. The Umpire sank quickly, trapping the rest of the crew on the seabed, 18 meters (60 ft) down. Water begin to rapidly flood the sub. Edward Young, a junior officer on the Umpire, later recalled, “In the half-darkness the men had become anonymous groping figures, desperately coming and going.” Young came across a man trying to open a watertight door, saying, “My pal’s in there.” Young could only tell the man that it was hopeless. “There’s no one left alive on the other side of that door.” Young waded to the wardroom in search of torches. After finding only one working torch, he returned to the control room, only to find it empty and the door to the engine room sealed. He could hear only the sound of water on the other side. Ultimately, Young and four others climbed up the conning tower to attempt escape. That was not as simple as throwing open the hatch, however. They had to flood the conning tower first to equalize the water pressure, meaning that they had to take their last breath even before filing out of the hatch one by one and swimming for the surface through the dark water. Two of the four men did not survive the ascent. The sinking of the Umpire claimed 22 lives, with Young and 14 others surviving. Young eventually became a distinguished submarine commander himself.

9 The Koosha-1

In October 2011, an Iranian ship called the Koosha-1 was helping to install an underwater oil pipeline in the Persian Gulf, roughly 24 kilometers (15 mi) out from Assaluyeh. On October 20, the ship capsized in bad weather and sank so fast that no distress signal could be sent. Six people drowned in the sinking, but rescuers still managed to save 60 others. However, bolted to the Koosha-1 was a hyperbaric recompression chamber, which held six divers when the ship went down. The chamber was pressurized to 60 meters (200 ft) at the time of the sinking, but the Koosha-1 came to rest on the sea floor 72 meters (236 ft) down, causing rescuers to fear that the chamber’s seals may have ruptured. Rescue efforts were further hampered by continuing bad weather, with winds reaching 30 knots. Finally, on October 23, the six divers were confirmed dead, after having run out of air. It is believed that they had enough air to last for two days at the bottom of the Gulf.

8 Blizzard River

You do not necessarily have to be out in the open ocean to suddenly and unexpectedly become trapped underwater. Such was the case in Agawam, Massachusetts, on August 7, 1999, at the Riverside Amusement Park (since redubbed Six Flags New England). At around 9:30 p.m., a raft on the park’s “Blizzard River” ride suddenly capsized. Eight belted-in passengers were left trapped facedown in a mere 0.8 meters (2.5 ft) of water. That was all it took. While park employees did manage to get some of the riders out before rescuers showed up, the riders (including at least two young children and a pregnant woman) nearly drowned, and several were left hospitalized in critical condition. One rider suffered a brain injury, and another was left with “permanent physical injuries.” In 2001, the eight riders sued the park owners and the manufacturers of the ride. The plaintiffs argued that the defendants should have known of the risk, since a woman died in a similar incident in Texas earlier in 1999. Also, the park employees seated the three heaviest passengers all on one side of the raft, only exacerbating the risk.

7 Chao Phraya River Ferry

On September 18, 2016, a ferry carrying over 100 people was traveling along the Chao Phraya River in Thailand. The passengers were primarily Muslim pilgrims returning to Nonthaburi Province after having attended a ceremony in Ayutthaya. Not far into the journey, the ferry turned to avoid another boat, which caused it to crash into a concrete bridge pillar. The lower deck of the two-level vessel ended up submerged. A chaotic scene ensued. Rescuers threw ropes to passengers swimming to shore, while others desperately tried to resuscitate victims pulled onto the riverbank. In the end, 27 people died, and roughly 40 others were injured. It took two days to pull most of the bodies out of the wreck. Thailand is known for a high rate of public transportation accidents, as safety regulations are barely enforced. In this case, the captain of the ferry was charged with reckless driving resulting in death.

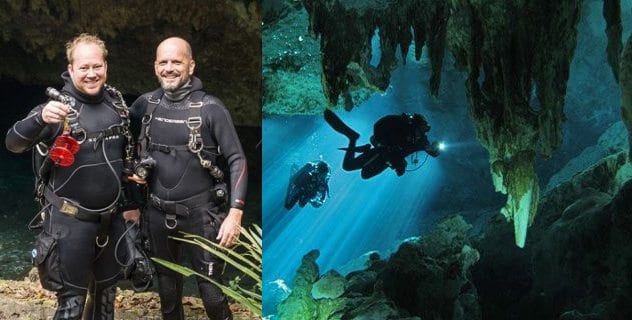

6 Patrick Peacock and Chris Rittenmeyer

Cave diving is a dangerous hobby, not meant for novice scuba divers. Diving in Eagle’s Nest, near Tampa, Florida, is even more so. Divers descend from what looks like an unassuming pond down to a network of 1.6 kilometers (1 mi) of passages, some as deep as 90 meters (300 ft) from the surface. “The Mt. Everest of cave diving” has claimed lives in the past. Patrick Peacock and Chris Rittenmeyer, two experienced cave divers, submerged into Eagle’s Nest on October 15, 2016. They had dived there the previous day without incident. The men knew the dangers, and when they dove into the cave at around 2:00 p.m., a safety diver named Justin Blakely waited closer to the surface for them. Peacock and Rittenmeyer were due to meet back up with Blakely at 3:00 p.m. The two did not show. Blakely checked back at the meeting location every 30 minutes until 6:00 p.m. when he called for help. Rescue divers were unable to find Peacock and Rittenmeyer that evening. A team of divers finally found the two men’s bodies near each other the next day, 79 meters (260 ft) down in an exceptionally dangerous part of the cave. Peacock and Rittenmeyer are the ninth and tenth people to die in Eagle’s Nest since 1981.

5 Twin Caves Rescue

Sometimes, cave diving mishaps do have happy endings. Such an ending occurred in another underwater cave in Florida, Twin Caves, in the summer of 2012. A father and his college-aged son and daughter decided to dive into the cave. The father was an open water scuba diving instructor, but none of the three were certified for cave diving. A group of cave divers exiting Twin Caves, as the open water trio entered, recounted how their open water style kicking disturbed lots of silt in the already generally silty cave. With visibility fast deteriorating, the cave divers quickly made sure their own lines were secure. Before long, the son bumped into one of them and was guided to the surface. The father soon emerged, but the daughter did not. The cave divers called for rescue. Fortunately, nearby was Edd Sorenson, an expert cave diver and rescuer, who right then was teaching a cave diving class. He ended his class and rushed to Twin Caves with his gear. There, he found “an 18-meter (60 ft) circle of mud where Twin was supposed to be.” Wasting no time, Sorenson secured his line and began a zigzag search in zero visibility. He soon found the daughter, her face barely above water in a small air pocket on the cave ceiling. She had left the pocket several times to try to surface, but she could not see a thing. Sorenson guided her out. Before 2012, only four lost cave divers had been successfully rescued, until Sorenson saved four people in that year alone.

4The AS-28

In another happy ending, seven Russian sailors managed to survive being trapped underwater for three days. In August 2005, the AS-28, a Priz-class mini-submarine, itself meant for rescue missions, was submerged roughly 70 kilometers (40 mi) south of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, the capital city of the Kamchatka Peninsula. An undersea surveillance antenna snagged the sub, and bits of fishing net became stuck in its propellers, stranding it 190 meters (623 ft) below the surface. Russian rescue attempts failed. Despite the AS-28 being stranded in a militarily sensitive region which includes the entrance to a submarine base, Russia was willing to appeal to other countries for help. Ultimately, a British submersible robot descended and cut the AS-28 free with its blades, allowing the vessel to surface. The seven sailors were taken to a hospital and were said to be in satisfactory condition.

3 Boy Survives Being Submerged for 42 Minutes

In 2015, a group of six boys jumped into a canal in Milan. Five came back up right away, but the sixth, a 14-year-old named Michael, became stuck, trapped in only two meters (6.5 ft) of water. It took 42 minutes before rescuers were able to free him. By then, his heart had stopped. Doctors managed to restart Michael’s heart. He was then placed on life support so that his heart and lungs could recover. For ten days, Michael remained in an induced coma and underwent extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), a technique which removes oxygen-depleted blood from the body and adds oxygen and warms it before returning it to the body. His right leg did have to be amputated below the knee, but 15 days after the accident, an MRI indicated that Michael’s brain was apparently undamaged. Amazingly, four weeks after Michael went into the canal, he woke up and spoke to his parents. He was completely coherent and could remember the events before the accident. He even asked for a mojito at one point. His doctor speculates that the cold water of the canal slowed down Michael’s bodily functions and likely played a factor in his survival.

2 The Johnson Sea Link

On June 17, 1973, a submersible called the Johnson Sea Link descended into the waters off Key West, Florida, with four men aboard: Archibald Menzies, Robert Meek, Edwin Link, and Albert Stover. Their goal was to retrieve a fish trap from the USS Fred T. Berry, a scuttled destroyer. They could not retrieve the trap, and at around 9:45 a.m., the Johnson Sea Link became tangled in a cable in the shipwreck, 110 meters (360 ft) underwater. The US Navy sent the USS Tringa to help. The ship arrived around six hours later, but it took time to determine the submersible’s exact location, as it had no distress buoy. To make matters worse, the submersible’s carbon dioxide scrubber failed in the meantime. By the evening of June 17, the temperature in the submersible had dropped to around seven degrees Celsius (45 °F), roughly the temperature of the surrounding water. The men were not dressed for such conditions, and the air was becoming less and less breathable. The first rescue attempt by the Tringa’s crew at around 11:00 p.m. was hindered by the shipwreck. Link and Stover were breathing from air tanks by this point, and the helium-oxygen mix they were breathing only exacerbated body heat loss. The atmospheric pressure inside the Johnson Sea Link had also increased greatly. By 1:12 a.m., Link and Stover were convulsing. Two further rescue attempts by the Tringa failed for various reasons, as did an attempt by another submersible. Finally, with the help of another ship, the Johnson Sea Link was able to break the surface at 4:53 p.m. on June 18. Link and Stover did not survive.

1 The Kursk

On August 12, 2000, Russia was conducting a large-scale naval exercise. Among the 33 vessels in the Barents Sea that day was the Kursk, an Oscar-class nuclear submarine. The Kursk was highly regarded. Boasts included that it could withstand a direct torpedo hit, that it could engage entire groups of US ships, and that it was unsinkable. It is believed that during the exercise, fuel leaking from a damaged torpedo triggered an explosion. The subsequent fire caused five to seven torpedoes to explode, ripping the sub open. It came to rest on the seabed 108 meters (354 ft) below the surface, roughly 135 kilometers (84 mi) off the coast of Severomorsk. Bad weather hampered Russian rescue attempts for days while they initially refused to admit that any disaster had occurred. Russia was also wary of accepting foreign help, given the advanced nature of the Kursk, but eventually relented. On August 21, they finally admitted that the crew was dead. Not all of the 118 men aboard the Kursk died immediately, however. Norwegian divers found that 23 men had survived for some amount of time in the Kursk’s aft compartment. There were reports of tapping sounds coming from the wreck on August 13. The tapping was said to have stopped on August 14. A letter found on Lieutenant Captain Dmitry Kolesnikov provided details of the trapped men’s final days, painting a picture of dropping temperatures, dimming lights, leaking water, and fouling air. Some men were badly burned, and others had been injured by flying debris. Kolesnikov wrote, “None of us can get to the surface.”