10 Strange Isolation

In Mexico, skulls from three areas were analyzed, dating back 500 to 800 years. The Sonora and Tlanepantla heads shared similarities but not those from Michoacan. The measurements were so different that they resembled a group that had developed in isolation for thousands of years. Yet no unbreachable landscape separated the regions. Michoacan was also just 300 kilometers (186 mi) away from Tlanepantla. For some reason, the Michoacan group did not interbreed with their neighbors and developed a distinctive skull shape. Researchers turned to human remains dating as far back as 10,000 years when Mexico received its first influx of people. These skulls came from Lagoa Santa and revealed something astonishing.[1] They, too, were so different that 10,000 years was not enough time to have evolved the skull features of South Americans today. The Lagoa Santa skulls likely shared an ancestor with modern South Americans but split 20,000 years ago outside the Americas. Conventionally, a single wave was thought to have settled the Americas. Several migrations from different areas make more sense. People isolated by tough language and cultural barriers offer some explanation for the Michoacan group. But why they remained genetically exclusive for millennia is not entirely understood.

9 The Manot Cranium

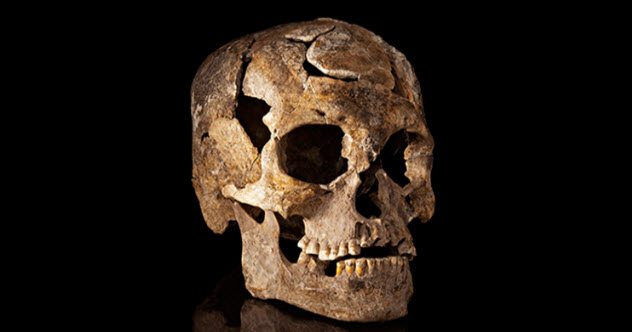

In 2008, a construction team was bulldozing an area in Manot in northern Israel when they found a cave. Inside was a unique piece of bone. It was a partial skull, but the cranium cap is priceless to archaeologists. Called Manot 1, it proves the scientific suggestion that modern humans left the African continent 60,000 to 70,000 years ago. Manot 1 is the only modern human skull found outside of Africa dating to the right time, around 60,000 to 50,000 years ago. The fragment belonged to a close cousin of the people who settled Europe and allows a rare glimpse of the first modern Europeans. Their brains were smaller. Compared to the volume of an average brain today, measuring around 1,400 milliliters, the Manot individual’s was 1,100 milliliters.[2] A bun-shaped protrusion at the back of the head is reminiscent of both ancient Europeans and more recent African fossils. However, it is unlike those who reside today in the Levant, a large area in the Mediterranean that also holds Israel. Manot 1 also places humans in a Neanderthal area during the time that previous studies predicted the beginning of interbreeding between the two species.

8 Life Expectancy Of Medieval Survivors

During medieval times, doctors could only prescribe bed rest for a skull fracture. Even if the patient survived, the prognosis remained bleak. A recent study—the first to use ancient skulls to gauge death risk connected to skull fractures—found that medieval survivors of head trauma had a shortened life expectancy. Three Danish graveyards from the 12th to the 17th centuries provided the heads when the plots were moved to make space for new buildings. Only men were chosen for the study because too few women had head wounds. Males who showed no healing (which meant they succumbed to the blows soon after) were also excluded.[3] Looking only at those who got better, researchers found that the chances of these ancient victims dying prematurely was about 6.2 times higher than a man who had never sustained a skull fracture. What finally killed these unfortunates cannot be said, but a hard life probably hurt them in the first place. Fights, violence, and work accidents contributed to injuries that likely left some men with brain damage, physical disabilities, or a propensity for dying sooner.

7 Head Hoarders

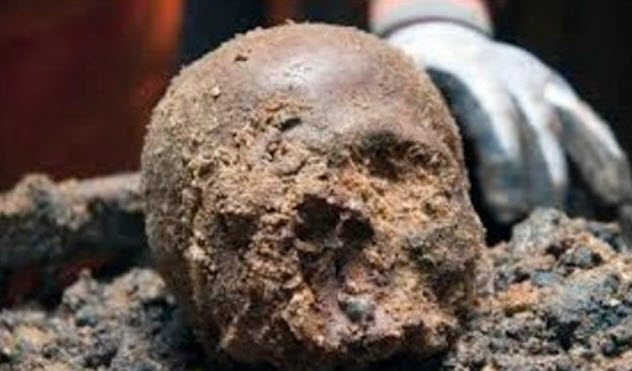

Taking heads as trophies is well-documented in Roman history. But in 1988, a surprising find proved that Romans also hoarded heads in Britain. In London, 39 skulls provided the first evidence of the practice. They dated to the second century AD when London experienced growth and peace. Discarded over the decades, the skulls showed that their owners did not share in the city’s prosperity. Not everyone’s gender could be determined, but forensics identified mostly young adult males.[4] Nearly all of them bore the marks of brutality—fractured face bones, cut marks from multiple wounds, and the distinctive damage of decapitation. They could have been beheaded as gladiators, criminals, or trophies on a faraway battlefield. Their origins remain as missing as their bodies. But they ended up in the open, still decomposing, as suggested by the chew marks of a dog on one skull. The remains were located near the Walbrook stream where hundreds of skulls have turned up over the centuries. The 1988 batch might prompt a reexamination to determine if more were the results of head-hunting.

6 Neanderthal Ear Inside A Human

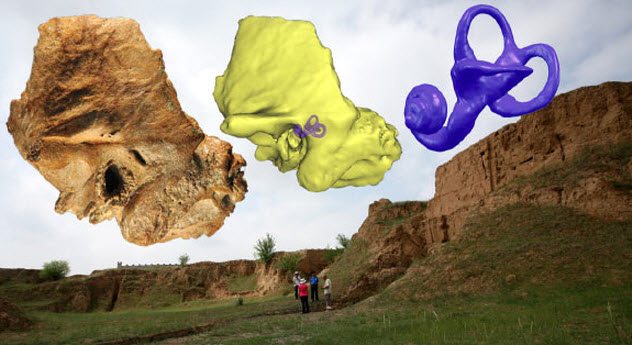

When a skull was found in 1979 in China, it was determined to belong to a late type of extinct human. More human teeth and bones found with it supported the identification. Called Xujiayao 15, after the area where it was unearthed, the head recently received renewed interest. At first, the researchers did not expect any surprises when they wheeled Xujiayao 15 through a CT scanner. What showed up next may sound mundane, but it shifts what scientists assumed were solid beliefs back into uncharted grounds. Inside the Homo skull was an inner-ear structure that was thought to be a trademark of Neanderthals. Yet Xujiayao 15 and the rest of the remains were determined to be distinctly non-Neanderthal. The unusual piece of anatomy is technically called the temporal labyrinth. Despite the fact that the skull belonged to somebody who died as long as 100,000 years ago, it should have resembled those of modern people. It raises questions about whether Neanderthal ear canals were unique to them, how Pleistocene humans migrated, and how they evolved. The discovery suggests that their story and biology were much more complicated than previously believed.[5]

5 The Arctic Lady

Anthropologists are keen to understand any ancient human presence in the Arctic because it is so unusual. Close to the Gorny Poluy River lies the necropolis of Zeleniy Yar which holds the remains of an unknown society of fishermen and hunters. The graveyard is a trove of mysterious information, but one 2017 find was a game changer. Previously, the approximately 36 graves were all male. Graves with children of both genders were also found. But there were no women. The latest grave revealed a body too degraded to determine the person’s sex by looking at the pelvis. However, her features were clearly feminine. The head was naturally mummified, and the delicate woman’s hair, eyelashes, skull, teeth, and skin were all intact.[6] It adds another twist to the Arctic civilization with unexpected links to Persia. (Zeleniy Yar previously yielded Persian bowls). Why the young woman appears to be the only adult female is not clear. But like the others, she was buried with her feet toward the river. At 900 hundred years old, the head is a unique addition to the rare mummies of Zeleniy Yar. This ancient skull was preserved by the copper sheeting that was wrapped around it.

4 The Real Fate Of The Canaanites

According to the Bible, God told the Israelites to eliminate the Bronze Age group known as the Canaanites, but the Israelites failed to do so. New DNA evidence confirms that this massacre never brought total extinction and that the Canaanites are still alive. Between 3,000–4,000 years ago, they lived in what are now Jordan, Syria, Israel, and Lebanon. Geneticists focused on Canaanite burials from Lebanon and extracted DNA from the bases of several skulls. Then they compared the genomes to living Lebanese.[7] As the region has witnessed many conquests and new peoples since the Bronze Age, the scientists expected few remaining genetic links. Remarkably, the results showed that modern-day Lebanese shared more than 90 percent of their ancestry with the Canaanites. That means that there is not much difference between the two populations and that the Canaanites would have resembled the Lebanese today.

3 The Elite Child

Another find may help researchers learn more about the enigmatic people who once inhabited the Arctic. The lone grave of a 1,000-year-old baby was found by accident when windy weather shaved off the top layer. At first, all that was visible was a copper bowl that was also from Persia. Fragments of the baby’s skull were found underneath the copper and belonged to an infant aged three years or younger.[8] There is no clue why he or she was buried in a place where there are no other graves. But the items gifted for the afterlife showed that the child’s family was very wealthy. In addition to the imported bowl, fur clothing, an ornate knife handle and sheath, pottery, and a temple ring were also found. Like the skull, the bowl was incomplete. But the erosion makes it difficult to pinpoint if the copper was ritually placed on the baby’s head as a fragment or whether the bowl was damaged by the wind. Researchers are also trying to figure out where the child’s clan originally came from and why they moved to the inhospitable Gydan Peninsula where the burial was discovered.

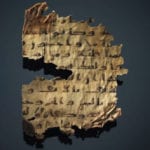

2 Gobekli Tepe Cult

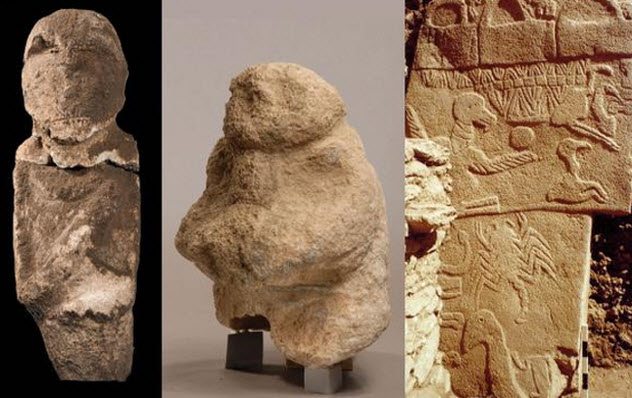

Gobekli Tepe is a famous Stone Age site in Turkey and also the world’s oldest temple. The mammoth ruins echo that of a complex hunter-gatherer culture which archaeologists still struggle to unravel. Recently, several elements merged to reveal another intriguing layer of the temple. It’s assumed that rituals occurred at Gobekli Tepe, but now it appears that a skull cult performed them, perhaps between suspended skulls.[9] This gory theory was realized when three skull pieces were discovered at the site. They were 7,000–10,000 years old. One had a hole drilled through it, and all three had unique linear carvings made by a flint tool. Other artifacts supporting Gobekli Tepe’s apparent obsession with decapitation include a beheaded human statue, a depiction of a head being given as a gift, stone skulls, and a headless figure on a pillar. The theme is not surprising. Other skull cults existed in the region during the same time. However, none match the decorations found at the temple. Or elsewhere in world, for that matter. One question is to whom the skull fragments belonged. Only additional discoveries will uncover if they were honored locals or desecrated enemies.

1 Women At The Huey Tzompantli

In 1521, the Spanish conquest consumed Mexico. Conquistador Andres de Tapia described the horror they encountered at a place later called the Huey Tzompantli. There, they witnessed the Aztecs’ love of sacrifice. De Tapia recorded buildings made of thousands of human skulls inside the capital, Tenochtitlan, which today is Mexico City. In 2017, archaeologists were working near a temple of Tenochtitlan when they found traces of the Huey Tzompantli. It was just one tower, but partial excavations counted 676 skulls in the edifice, which was about 6 meters (19 ft) in diameter.[10] The surprise came when the skulls were analyzed. Historians who were contemporaries of de Tapia described the Huey Tzompantli and similar places as something done by the Aztecs and other Mesoamericans to display the heads of sacrificed enemy warriors. The tower delivered a first: Between the males were women. Proving historical accounts even more wrong were the children tucked away between the adults. Something else happened at the site for which no explanation exists. Finding women and children where there should only have been young men suggests that Aztec sacrifice rituals were more complicated than initially believed. They are still not fully understood. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages