If you live in a place where humans have built civilizations for at least a few hundred or thousand years, you’ll notice carvings on buildings, see peculiar costumes at festivals, and hear and read stories that feature curious motifs and characters. These artifacts of our cultures are all around us. Here’s a list of some of the coolest folk motifs from around the globe.

10 The Green Man, Britain

The Medieval era in Europe was a time of great transition. At the beginning, the Western Roman Empire was falling, and Christianity was on the up and up. By the end, we welcomed the Renaissance, and the seeds of the Enlightenment were beginning to sprout. However, some older traditions—elements of a pre-Christian time—stubbornly hung around. In Britain, people still danced around maypoles, continued to use ancient languages, and told tales from before the coming of the gospels. They clung to superstitions, habits, and imagery from this by-gone age. Still do. The Green Man, the ever-present foliate head that gurns at worshippers from carved wooden elements and stone pillars in many churches, is the foremost example of this. The figure is a remnant of the nature-focused religious practices that pre-date the Roman occupation of Britain, an omen that brings good fortune for harvests and warns man that to fully leave nature is to invite it as an enemy. It may seem strange to the modern devoted Protestant Christian to see such blatantly paganistic iconography adorn the architecture of churches. But one must keep in mind that to convince large numbers of people of the value of the “new,” one must bring along the positive aspect of the “old”—the inhabitants of pagan Britannia needed a bit of nostalgia. Found all over Great Britain, this ancient symbol proves that even on a building as ancient as a medieval-era cathedral, older elements come along too.[1]

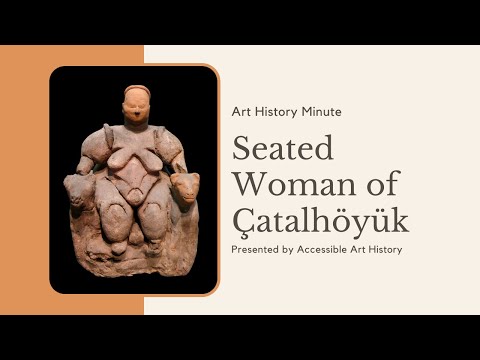

9 Potnia Theron, the Mediterranean and Near East

The Eastern kissing cousin to the Green Man is the image of the “Master of Beasts,” a cross-cultural depiction of a man holding wild animals aloft as though their master. Unlike its Brythonic cousin, the Master of Beasts shows mastery, or an interwoven relationship, with animals instead of nature in general (or plant-life, more specifically). But this image is rarely as cool as depictions of the “Potnia Theron”—the Mistress of Beasts. The earliest example of this motif dates from 6,000 BC, a clay figurine depicting a seated female figure flanked by two lionesses uncovered in the Neolithic city of Çatalhöyük in modern-day Turkey. This image spread all over the Mediterranean and Near East. It symbolizes mankind’s dominance over animals—defense from husbandry and hunting…possibly. Truth be told, we don’t know the true meaning. Depictions of this figure are found in Mycenaean Greek religion—the image used to signify the Goddesses Artemis (goddess of the hunt and the wilderness) and Cybele. She is the fascinating goddess that found her way into the Greek pantheon from Asia Minor, near Çatalhöyük. She was viewed as a “foreign” mother goddess and, rather uniquely in ancient Greece, had a sect of castrated priests who followed her.[2]

8 Nain Rouge, Detroit, Michigan

Now to a more modern form of folk culture. In the city of Detroit, Michigan, there is a symbol that pops up all over the famed “Motor City,” one that evokes dread in little kids who hear stories of his exploits and joy for partygoers during the springtime Marche du Nain Rouge parade. And (unfortunately) a hipsterish delight for frequenters of the city’s trendier businesses that sport the image as a “keeeewl retro mascot, bruh.” Who can blame them? A tradition that began to fall out of favor: check. Partially derived from indigenous culture: BIG check. Looks like the devil, thus allowing for them to show antipathy to Abrahamic religions: GET THEE ALONGSIDE ME, BABY SATAN! Love from annoying, mustachioed skinny-jean sporting losers aside, this devilish little imp is a mainstay in Detroit culture, part of the area’s consciousness since way back when it was a French settlement. Popular folk history suggests the Nain Rouge is probably derived from the Norman-French hobgoblin known as a “lutin” merged with local Native American mythical beings—the type of syncretic figure found all over the Americas. Both sets of traditions describe small, demonic beings that seek to cause mischief and bring bad luck. The aforementioned springtime parade is designed to drive this portent of bad luck from the city for the rest of the year.[3]

7 Onryō, Japan

Sometimes ancient traditions get an unexpected, and often very welcome, reimagining in contemporary culture. The belief in ghosts and spirits, especially malevolent ones, has a long and storied history in Japan. A will for vengeance against those who have wronged you is a deep and abiding part of traditional Japanese culture—to dishonor is unforgivable. The unfortunate thing about humans is we are weak, squishy meat sacks that can easily be dispatched with a well-aimed chop from a katana. How could such a bifurcated individual get their deserved vengeance? They become a ghost. And, if long-established Japanese tales are anything to go by, they do it a lot. The coolest thing about this folk motif is how it has moved into modern culture. One of the strongest traditions of contemporary horror is found in the Land of the Rising Sun. Nowhere is this more apparent than in J-Horror movies—blockbusters like Ringu and Ju-On especially. Both these franchises have something in common: they spawned questionable Hollywood re-makes and feature an Onryō as the primary antagonist—creepy female ghosts with long, black hair and white funerary attire, inspired by the costumes worn by such characters in Edo-era Kabuki performances. The influence of these ancient Japanese monstrosities can be seen in almost any post-2005 supernatural horror flick, arguably spurring the move away from the slasher movie genre’s dominance at the box office. And all that from a clutch of spooky stories from feudal Japan…[4]

6 El Hombre Caiman, Colombia

Most of these folk motifs have a cool story that goes along with them, even if many of them have been lost in the mists of time. One of the best examples of this comes from the Caribbean-facing coast of Colombia: the legend of the “Alligator Man.” The story tells of a young man who lived near the Magdalena River. All this horny little brute loved to do was spy on the women as they came to the river to bathe. He found a good spot in the thick undergrowth to conceal himself and watch the ladies in the river. One day, he was spotted. He fled deep into the forest, where he came upon a witch. He begged the witch to help him conceal himself more effectively so he could continue to stare at naked women. The witch agreed and brewed up two potions for the young horn-dog—one that’d turn him into an alligator (so he could lie down on the riverbed and look up at all the bathing beauties) and one to turn him back into a man. The pair went down to the river to test out the potions. When the witch saw that the first one had worked—the man was sloshing around in a reptilian form—she got very excited, dropping the other potion into the water. Unfortunately, the potion only turned the man’s upper half back, leaving his nether regions scaly and green. When the man angrily demanded the witch solve this problem, she denied him, cursing him to remain that way forevermore. What a yarn! So cool is this little folk tale that the town of Plato near the Magdalena River has a huge statue of the semi-crocodilian perv. And just when you thought mermaids were always sexy…[5]

5 Shetani, East Africa and the Island of Zanzibar

Dog-headed demons, hideous stunted hags, strange Dali-esque elephants; these are the sorts of carved sculptures you can expect to find everywhere in Mozambique, Tanzania, parts of Kenya, and the island of Zanzibar. These are the Shetani—the “devils.” In fact, they are derived from the same Semitic root that gives rise to the Islamic “Shaitan” and the Christian “Satan.” Beyond these cool-looking sculptures and creepy folk tales, many modern East Africans believe in the Shetani very seriously. Recall the mass-hysteria-fueled panic that occurred on Zanzibar in 2001 when locals claimed that Popo Bawa, a bat-winged Shetani, was attacking victims. The BBC reported: “The ghost or genie goes by the name of Popo Bawa, and people believe that it sodomizes its victims, most of whom are men.” Yeesh. Cultic practices surrounding these beings also occur across East Africa, proving that some ancient traditions can remain vibrant in more than just architecture and song.[6]

4 Woyo Tribal Masks, Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola

These incredibly expressive masks are worn by the Woyo people, a group living on the Atlantic coast of Central Africa. They are worn at ritual dances by the “ndunga,” the group tasked to keep societal order and maintain the tribal laws. Imagine your local copper pulling you over on the highway, tapping on your car window wearing one of these masks. Watch this video on YouTube What’s scarier is that these men will don these masks to carry out their duties—tracking down suspected criminals and witches, those blamed for causing natural disasters like droughts or flooding, even poor harvests. Each mask is said to have its own unique “character,” usually revealed during ritual dances.[7]

3 The Night Hag, Worldwide

There are very few traditions, motifs, or stories that can be found the world over. However, an extremely curious (and, when you think about it, terrifying) character that shows up all over the globe is the “Night Hag” or “Old Hag.” This wizened, malevolent old woman appears near people at night, scaring them and pressing down or sitting on their chests until they struggle to breathe. So, sleep paralysis, right? Probably, but does that make you less scared? If you found out that poltergeists were just normal, common-or-garden-variety prion diseases, would that make you less afraid? In East Asia, it’s blamed on Buddhist monks and nuns, throwing their spirit forth to the dream realm to paralyze wicked people. In Brazil, the hag lives on the roofs of houses, ready to descend into bedrooms and stand on the bellies of those who’ve eaten too much. Her name is more frightening than Night Hag—”Pisadeira” or “She who steps.”[8] Ugh.

2 Manaia, New Zealand

Take a look at an image search of these Maori carvings—what do you see? A serpent? A bird-headed humanoid? A man in profile? Dinosaur? The answer is nobody knows what these enigmatic motifs really depict, despite turning up a lot in traditional carvings. The word itself offers no clue. If you look it up in a Maori dictionary, the meaning varies from “a grotesque beaked figure sometimes introduced in carving; ornamental work, a lizard; the sea-horse; a raft.” Is that what you see, a raft? Enjoy drowning… In related Polynesian languages, there are similar words that mean “embellishment.” So, these carvings are…just carvings? Filler for corners on lintels and pillars? Nah, they must mean something, or the style wouldn’t be so identifiable and common. Whatever they signify, however, has been long forgotten. Still, they look awesome.[9]

1 Bhoma, Bali

We started this listicle with the traditional European figure The Green Man and the Meditteranean’s Pontia Theron. On the island of Bali, you’ll find a similar figure that adorns temples and other buildings, symbolizing much of the same themes as man’s interactions with the natural world. The main difference? Look how cool this thing looks; it’d eat the Green Man whole, plus the Mistress and her beasts too! In the island’s Hindu tradition, the Bhoma is considered the son of Vishnu and the earth goddess Pertiwi. The figure is a nature spirit of sorts, considered “King of the Jungle” (take that, lions). Bhoma is also considered a guardian spirit, keeping watch over the sacred forests at the foot of holy mountains. And does a bloody good job of it too—you don’t want to mess with that thing.[10]