The Tortoise and the Hare as been interpreted, retold, and referenced by many different people and in numerously different ways. This list looks at ten instances.

In classical architecture, a pediment is a large, flat isosceles triangle that rests on the top of stone columns. The form is characteristic of ancient temples and, somewhat incongruously, modern civic buildings. The east façade (the back) of the United States Supreme Court Building in Washington D.C. boasts such a feature, which was sculpted in marble by Hermon Atkins MacNeil in 1933. It is here you will find, above the inscription “Justice, the Guardian of Liberty” a depiction of the tortoise and the hare. The two animals are peripheral elements in a broader, more complex portrayal that includes at its center Moses holding the ten commandments, so they can be easily missed – the tortoise tucked into the far right corner and the hare into the far left. Yet they are there, reminding onlookers in a subtly assuring way that justice, like the steadfast tortoise, is indeed firm and true.

In the original cartoon series Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Season 3 (1989), episodes #50 and #52 “Usagi Yojimbo”/“Usagi Come Home,” the turtles meet a rabbit ronin (master-less warrior) from another dimension. His name is Miyamoto Usagi and he’s the main focus of his own series of comics by Stan Sakai. Besides the obvious allusion, this relationship has very little to do with Aesop’s fable, but is list-worthy on the grounds that it is a prime example of how enduring and pervasive the allusion is. Usagi toys were sold as part of the Ninja Turtles collection, and the character became a regular in the second batch of TMNT cartoons that began in 2003, appearing in several episodes throughout the series. Usagi Yojimbo is not to be confused with Hokem Hare, another much lesser character from Season 5 of the original series who in episodes #106 and #107 “The Turtles and the Hare”/“Once Upon a Time Machine” accompanies the turtles as they travel into the future to team up with their future selves to defeat the future Shredder.

Aesop’s fables got a nice retelling in 1668 from the French poet and fabulist Jean de La Fontaine. La Fontaine’s “Le Lievre et la Tortue” was one part in a hefty volume he wrote and presented as a gift to Louis XIV’s six-year-old son Louis, Le Grand Dauphin. This version is 36 lines long and has been translated into English many times, rhyming with varying degrees of success. It is noteworthy in that it has the tortoise challenging the hare outright, without any instigating at all on the hare’s part. The tortoise also, rather unnecessarily, mocks the hare at the finish. La Fontaine’s version of Aesop’s fables got their own boost in popularity when they were later illustrated by 19th century French caricaturist J. J. Grandville. Grandville’s colorless drawing of the race depicts the tortoise sprinting across the finish oddly on his two hind legs like a person (oddly because the creature isn’t anthropomorphized in any other way at all), with the naturally-styled hare in close pursuit.

Lord Dunsany, an Irish dramatist, fantasist, and satirist, had his own adaptation of the story called “The True Story of the Hare and the Tortoise,” published in his Fifty-One Tales in 1915. In it, the hare is at the outset very unwilling to race while it is the tortoise who exhibits all of the confidence in victory. The hare only agrees to do it because all the other animals are on the verge of starting a war over the question of which is faster. Midway though the race, the hare, with an enormous lead, decides the contest is pointless and quits, allowing the tortoise to win. When the other animals determine the tortoise to be the champion, it is only to their downfall as they later send him to retrieve help for a forest fire in the belief that he’s the fastest animal. This interpretation, while keeping the outcome the same, reverses the two roles. The hare now appears as the more dignified figure as he refuses to plainly defeat a vastly inferior opponent, and it seems as though he falls asleep out of pure disinterest as opposed to stupidity. The other animals thus become the oblivious and unwise ones, to their unfortunate demise.

Ray Harryhausen was a special effects artist who pioneered in the technique of stop-motion clay animation. Among his most renowned creations are the octopus in It Came from Beneath the Sea, the Cyclops in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, and the skeleton army in Jason and the Argonauts. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, before he made a big name in Hollywood, he sharpened his teeth as an animator by producing short-subject, low-budget, seemingly (to us now, but not then) amateur-quality animations based on assorted nursery rhymes and fairy tales. One of the projects he started in those days but couldn’t finish was The Story of the Tortoise and the Hare. It wouldn’t be until 2003, more than 50 years after its conception, that it would be finally completed with the help of Seamus Walsh and Mark Caballero. These individuals, out of sheer admiration for Harryhausen, initiated the revival, even going as far as restoring his original puppets, insisting on using a vintage camera from the era, incorporating what remained of Harry’s old original footage, and submitting to Harryhausen’s direction in all other aspects of production. Their version, while very traditional in most respects, is also fairly peculiar as only the hare walks upright and wears clothes while the tortoise remains on all fours – like Grandville’s depiction only the opposite. As a side note, this curiosity is also true of an illustration by Arthur Rackman from his Aesop’s Fables, published in 1912.

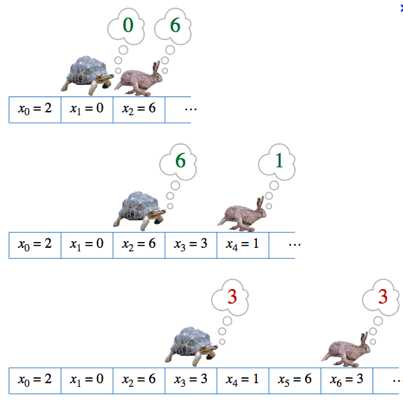

The Tortoise and the Hare Algorithm is another name for Floyd’s cycle-finding algorithm, named after Robert W. Floyd, its inventor. Neither computer science nor mathematics is the strong suit of this author, so an extremely unsophisticated explanation of it will have to suffice. The general idea with the algorithm is that the tortoise and the hare are names given to two pointers which move and different speeds through a sequence of values, the hare moving two steps through the sequence for every one step the tortoise moves. The purpose is to detect a loop, if one exists, in any iteration or list. The inspiration behind it, or at least behind half of the imagery involved in its name, goes back to an ancient paradox about Achilles and a tortoise. The paradox goes as follows: Achilles gives a tortoise a head start in a race, but even though he can run faster than the tortoise he can theoretically never surpass it because every time he reaches a point where the tortoise once was, the tortoise will always have advanced farther in the meantime, thus remaining in the lead forever.

In 1941 Bugs Bunny was a still evolving cartoon character, not yet having arrived at exactly how we recognize him today, but feisty nonetheless. His appearance in “Tortoise Beats Hare” marked the first of three showdowns he would have against Cecil Turtle, a character known exclusively for these three races against Bugs, none of which he wins fair-and-square. Watch this video on YouTube To summarize, in “Tortoise Beats Hare” Cecil outright deceives Bugs and creates only the illusion that he has defeated him (which we might suppose contains a lesson of its own; that brains overpower brawn). In the 1943 sequel “Tortoise Wins by a Hare” Bugs gets bested at his own game yet again and in the third meeting, which is sort of a reboot as both characters seem to be unaware of the previous two races in this one, Bugs finally emerges the victor but with a twist ending. Of course, each of these represents a less-than-traditional take on the fabled race, but they’re fun and funny, if for no other reason than they give us the bizarre prospect of a turtle taking off his shell as if it were clothes.

Jan Wildens was an early 17th century landscape painter from Antwerp, modern-day Belgium: hub of the Flemish Baroque style of that period. His oil-on-canvas titled The Tortoise and the Hare, from Aesop’s “Fables” gives us a serene and pastoral scene consisting of a path and a brown hare dashing in from the bottom left corner. The tortoise is absent – in fact one might not even know the subject matter were it not for the title – and therein lies the genius. At the twilight of the race, the tortoise is already far and gone, and it is too late for the frightened hare.

Nancy Schön is a world-class sculptor who specializes in the zoological and the literary. Her public art is the type people are welcome to touch, feel, lean on, and sit on, which most people find it difficult to resist doing, particularly children. In 1993 she unveiled her bronze “Tortoise and Hare” in Boston (her hometown) in tribute of the Boston Marathon, then in its 97th year. The piece is more correctly two separate sculptures as the smiling tortoise is trudging along about fifteen feet ahead of the hare who has stopped to scratch his ear. It is located in Copley Square between Boylston, Huntington, and St. James, near the finish line of the annual marathon. It is an elegant work, much more shrewd and unpretentious than the Tortoise and Hare sculpture found at Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx, New York City, a couple hundred miles to the south.

“The Tortoise and the Hare” was an 8-minute animation created by the Walt Disney company as part of their Silly Symphonies brand from the 1920s and 1930s. The cartoon introduced the characters eponymous Max Hare and Toby Tortoise, sporting a white sweatshirt and red necktie respectively. The film won the 1934 Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film. To a very small extent the story diverges from the standard tale in that the hare doesn’t get caught behind because he stops to rest, but rather because he is preoccupied with flaunting his great ability to a group of female bunnies. It remains loyal to the fable in all other critical ways, however, keeping the moral in tact while still adding its own unique and vintage attributes. It’s almost a little too archaic in its pure form. Almost, that is, not quite. It’s perfect the way it is. Even though this production predates Bugs Bunny by nearly decade (actually, Max Hare is considered to be a primary influence, if not the direct forerunner, to Bugs), the animation is far superior and the race’s finish, somehow, manages to be a lot more thrilling than expected.